Brutalism: A New Visual Language

Brutalism: Functionality over Aesthetics

In tandem with our re-OpenLab ‘Architextures’ music series, here we look at Brutalism, an architectural style that emerged in the mid-20th century, characterized by its stark, uncompromising use of raw concrete and an emphasis on functionality over aesthetics.

The term “Brutalism” is derived from the French phrase “béton brut,” meaning raw concrete, which was the preferred material of many of the movement’s architects. Brutalism gained popularity during the post-World War II period, when cities around the world faced the challenge of rebuilding damaged infrastructure and providing affordable housing to rapidly growing urban populations. It became synonymous with bold, monumental buildings that prioritized social utility, creating a new visual language for civic structures, educational institutions, and housing complexes.

All of our content is free to access. An independent magazine nonetheless requires investment, so if you take value from this article or any others, please consider sharing, subscribing to our mailing list or donating if you can. Your support is always gratefully received and will never be forgotten. To buy us a metaphorical coffee or two, please click this link.

Table of Contents

Origins and Evolution of Brutalism

The origins of Brutalism can be traced back to the early works of Swiss-French architect Le Corbusier, particularly his Unité d’Habitation in Marseille (1952), which is widely regarded as one of the first examples of the Brutalist style. However, the term “Brutalism” was coined in the 1950s by British architects Alison and Peter Smithson, who sought to create a new architectural approach that was honest, raw, and socially responsible.

The Smithsons rejected the decorative elements of previous architectural movements in favour of designs that emphasized function and materiality. Their work, along with that of other architects such as Ernő Goldfinger and Paul Rudolph, would come to define the Brutalist aesthetic in the 1960s and 1970s.

“Brutalism tries to face up to a mass production society and drag a rough poetry out of the confused and powerful forces which are at work.”

Alison Smithson

New Forms and Structural Techniques

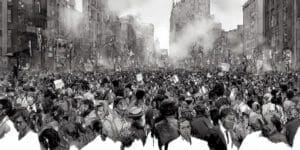

Brutalism emerged at a time when many Western nations were in the process of rebuilding following the devastation of World War II. With cities across Europe and North America in need of rapid reconstruction, architects embraced the practicality and affordability of concrete as a building material. Concrete’s versatility allowed architects to experiment with new forms and structural techniques, creating buildings that were both functional and expressive. The post-war period was also marked by a belief in architecture’s capacity to shape society. Brutalist architects, in particular, saw their work as part of a broader project to create egalitarian, democratic spaces that could serve the public good.

In its early years, Brutalism was primarily associated with civic and social housing projects. The style became a hallmark of post-war urban planning, with many Brutalist structures designed to address the pressing need for affordable housing in rapidly growing cities. The movement spread from Europe to North America and beyond, influencing the design of government buildings, universities, and cultural institutions. Despite its noble intentions, however, Brutalism faced significant backlash by the late 1970s. The stark, fortress-like appearance of many Brutalist buildings, combined with their association with large-scale public projects, led to widespread criticism. The style became synonymous with urban decay and neglect, and many Brutalist structures were demolished or fell into disrepair.

“We are trying to get at the idea of community architecture, in which we emphasize the quality of life rather than the quantity of space.”

Peter Smithson

Iconic Examples of Brutalist Architecture

The Unité d’Habitation by Le Corbusier

The Unité d’Habitation in Marseille, designed by Le Corbusier and completed in 1952, is widely regarded as one of the most iconic examples of Brutalist architecture. The building was conceived as a “vertical garden city,” designed to house over 1,600 residents in a self-contained community that included shops, a school, and recreational facilities. Le Corbusier’s design was based on his principles of urbanism, which emphasized the importance of light, space, and greenery in modern living environments. The use of rough-cast concrete, or “béton brut,” became a defining feature of the building’s exterior, giving it a bold, monumental appearance.

The Unité d’Habitation not only influenced subsequent Brutalist projects but also set the tone for post-war housing developments across Europe. Its innovative use of space, materials, and design reflected the social ideals of the time, offering a solution to the housing crisis in many war-torn cities. Despite its utopian vision, the Unité d’Habitation has faced criticism for its austere, fortress-like appearance and the sense of isolation it creates for its residents. Nevertheless, the building remains a landmark in architectural history, and Le Corbusier’s vision of communal living continues to inspire architects and urban planners today.

*All book images suggest books that offer in-depth insights into the history, design philosophy, and impact of Brutalism and all book images Open a New tab to our Bookshop.

**If you buy books linked to our site, we get 10% commission from Bookshop.org, whose fees support independent bookshops.

The Barbican Estate in London

The Barbican Estate in London, designed by Chamberlin, Powell, and Bon and completed in the 1970s, is one of the most famous examples of Brutalist architecture in the UK. The estate was built as part of a broader effort to revitalize the City of London, which had been heavily bombed during World War II. The complex consists of residential towers, cultural institutions, and public spaces, all designed with the Brutalist emphasis on raw concrete and monumental forms. The Barbican’s design reflects the movement’s commitment to creating functional, inclusive spaces that serve the needs of modern urban life.

Despite its controversial appearance, the Barbican Estate has become one of London’s most iconic landmarks. The estate is home to the Barbican Centre, a major cultural hub that includes concert halls, galleries, and theatres. The combination of residential, commercial, and cultural functions within a single complex reflects the Brutalist ideal of creating self-contained, integrated urban environments. While the Barbican has faced criticism for its imposing design and brutal aesthetic, it has also been praised for its ambitious vision of urban living. Today, the estate is considered one of the most successful examples of post-war Brutalist architecture, and it continues to attract residents and visitors alike.

Boston City Hall

Boston City Hall, designed by Kallmann McKinnell & Knowles and completed in 1969, is one of the most controversial examples of Brutalist architecture in the United States. The building’s bold, angular design, characterized by its rough concrete façade and geometric forms, was intended to reflect the democratic ideals of transparency and accessibility. The architects sought to create a civic building that would stand as a symbol of the city’s commitment to public service, with a design that emphasized openness and interaction between government and citizens.

However, Boston City Hall has been the subject of intense debate since its completion. While some have praised the building’s innovative design and its reflection of Brutalist ideals, others have criticized it as cold, uninviting, and even oppressive. The stark, fortress-like appearance of the building has led to calls for its demolition on several occasions, though it has also garnered a dedicated group of supporters who argue that it represents an important chapter in the city’s architectural history. Despite the controversy, Boston City Hall remains a significant example of Brutalist architecture and continues to provoke discussion about the role of design in shaping civic spaces.

Brutalism Today: Reappraisal and Legacy

In recent years, Brutalism has experienced something of a revival, as architects and designers have begun to reappraise the movement’s legacy. What was once dismissed as ugly, oppressive, or outdated is now being recognized for its boldness, ambition, and social purpose. Brutalist buildings that were once slated for demolition are being restored and celebrated for their architectural significance. In particular, Brutalism’s focus on functionality and its embrace of raw, honest materials have found new resonance in an era of environmental consciousness and minimalist design.

Today, Brutalism is viewed as a critical part of the architectural canon, and its influence can be seen in contemporary projects that emphasize sustainability, social responsibility, and a rejection of unnecessary ornamentation. While the style may never regain the widespread popularity it enjoyed in the 1960s and 1970s, its principles continue to inspire architects and urban planners who are committed to creating functional, socially conscious designs. As cities around the world continue to grapple with issues of affordable housing, environmental sustainability, and urban regeneration, Brutalism’s legacy offers valuable lessons about the role of architecture in shaping society.

The Future of Brutalism

The future of Brutalism is likely to be defined by its ability to adapt to contemporary concerns, particularly in relation to sustainability and social equity. Brutalist buildings, with their emphasis on durability and functionality, are well-suited to the demands of a rapidly changing world. As architects and planners seek to create more sustainable and inclusive urban environments, the lessons of Brutalism may become increasingly relevant. The movement’s focus on creating spaces that serve the public good, rather than merely aesthetic considerations, offers a model for how architecture can respond to the pressing challenges of our time.

Challenging conventional notions of Beauty and Design

Brutalism remains a polarizing yet profoundly influential movement in the history of architecture. From its origins in the post-war period to its contemporary resurgence, the movement has consistently challenged conventional notions of beauty and design. While Brutalism may never be universally embraced, its legacy endures in the bold, socially conscious buildings it has left behind and the architects it continues to inspire.

“Concrete is the language of Brutalism. It is not decorative, but rather an honest expression of structure and form.”

Paul Rudolph

Leave a Comment