Dada, Art and Anti-Art

In tandem with our re-OpenLab ‘Architextures’ music series hosted by Francesca, here we look at the Dada movement which detonated the very notion of what art could be. Born in the shockwaves of World War I, from its first performances at Zurich’s Cabaret Voltaire in 1916 to its explosive photomontages in Berlin and the readymades in New York, Dada rejected the rationalism, nationalism, and bourgeois taste that artists believed had helped usher Europe into catastrophe. It replaced those values with provocation, chance, absurdity, and a gleeful irreverence that continues to shape experimental culture today.

Dada was not a single style so much as a tactic – a way of operating against the grain of common sense – spreading in nodes (Zurich, New York, Berlin, Cologne, Hanover, Paris) through artists, poets, designers, and filmmakers. If modern art had a big bang, Dada was the flash.

All of our content is free to access. An independent magazine nonetheless requires investment, so if you take value from this article or any others, please consider sharing, subscribing to our mailing list or donating if you can. Your support is always gratefully received and will never be forgotten. To buy us a metaphorical coffee or two, please click this link.

Table of Contents

*All book images suggest books that offer in-depth insights into the history, design philosophy, and impact of Feminist Art and all book images Open a New tab to our Bookshop.

**If you buy books linked to our site, we get 10% commission from Bookshop.org, whose fees support independent bookshops.

From Zurich’s Cabaret to a Transatlantic Shockwave

Zurich, 1916. Switzerland’s neutrality made it a magnet for exiles of every political stripe. In a cramped café space, the poet Hugo Ball and the performer Emmy Hennings founded the Cabaret Voltaire – a nightly crucible of noise poetry, masked recitals, improvised dance, anti-war satire, and irrational theatrics.

Close collaborators included Tristan Tzara, Hans (Jean) Arp, Sophie Taeuber-Arp, Richard Huelsenbeck, and Marcel Janco. In this small room, the group declared cultural war on the very idea of “civilized” art. They published little magazines, mounted chaotic evenings, and issued “manifestos” that sounded like detonations rather than reasoned arguments.

New York, 1915–17. Across the Atlantic, a parallel strain of anti-art emerged around Marcel Duchamp, Francis Picabia, and the Arensbergs’ salon. Duchamp’s “readymade” strategy – selecting mass-produced objects and designating them art – was a conceptual torpedo aimed at taste, craft, and the aura of the unique masterpiece.

When Fountain (a signed urinal) was submitted to the Society of Independent Artists exhibition in 1917 and refused, the scandal canonized Dada’s idea that artistic meaning is constructed by context and choice rather than by hand-skill alone.

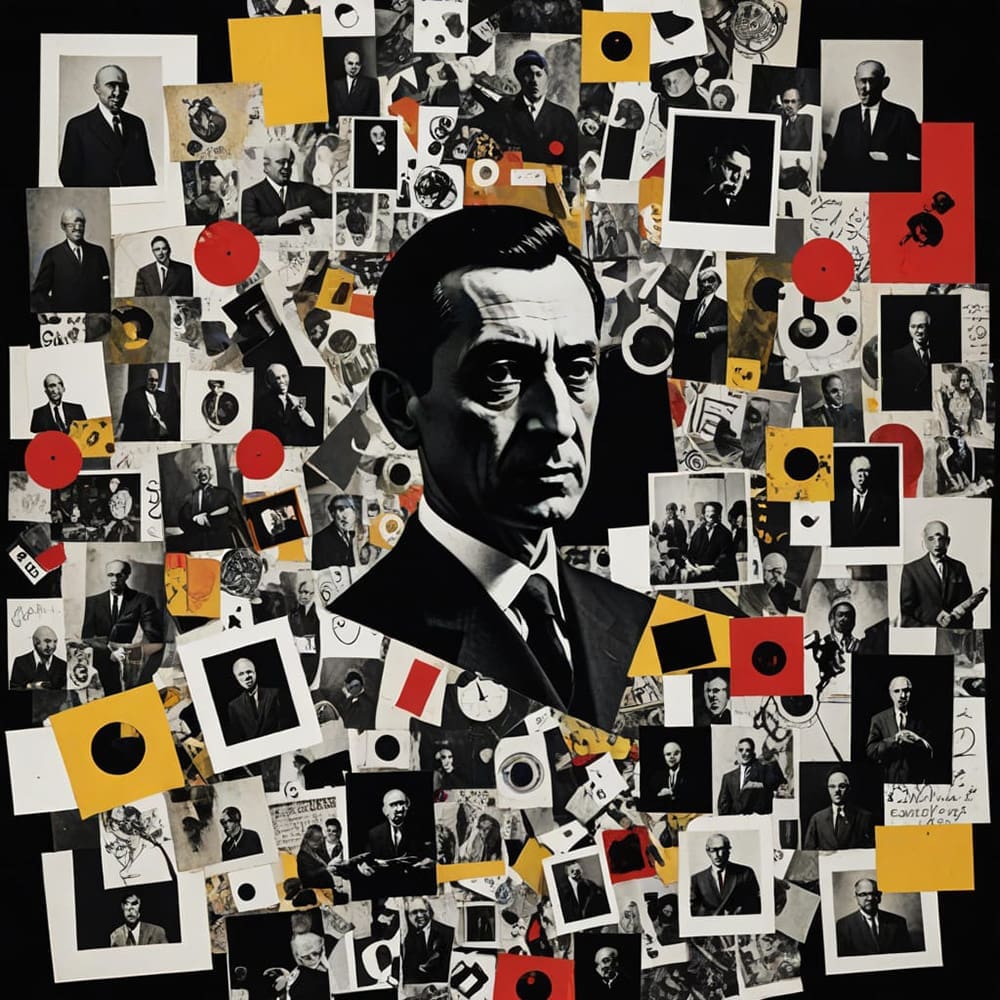

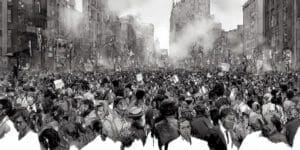

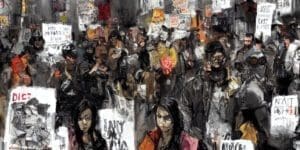

Berlin, 1918–20. After the war, Dada became explicitly political in Germany. Artists such as Raoul Hausmann, Hannah Höch, John Heartfield, and George Grosz turned to photomontage – slicing up newspapers, publicity stills, and official portraits to indict militarism, capitalism, and reactionary politics. Their exhibitions were staged like visual ambushes; placards and mannequins mocked the very idea of a respectable salon. The use of mass media – photographs, headlines, typography – prefigured contemporary tactics of remix and meme culture.

Cologne, Hanover, Paris. In Cologne, Max Ernst and Johannes Baargeld ran a Dada show in a courtyard with an entrance via a public restroom; the police shut it down. In Hanover, Kurt Schwitters developed “Merz,” a scavenger-aesthetic that fused collage, poetry, and assemblage into a singular personal cosmos.

In Paris around 1920, Dada’s provocations set the stage for Surrealism, as André Breton and others re-channelled Dada’s antirational energy into psychic automatism and dream logic. By the mid-1920s, Dada’s protagonists had scattered or transformed, but its methods – appropriation, performance, anti-aesthetic humour – became the DNA of avant-garde practice.

What Made Dada Dada

At its core, Dada was a revolt against the logic, order, and refinement that many artists believed had helped lead the world into war. Rejecting the idea of “high art” as a civilising force, Dada embraced absurdity, nonsense, and chance as deliberate strategies. The movement sought to dismantle the prestige of the masterpiece by treating art not as a commodity or object of reverence, but as a moment of disruption. Works could be as fleeting as a performance, as ephemeral as a collage of newspaper clippings, or as confrontational as a mass-produced urinal signed with a pseudonym. In place of the solemnity of galleries, Dada proposed the energy of cabarets, the chaos of street actions, and the visual anarchy of printed manifestos.

“Dada means nothing.”

Tristan Tzara

Central to Dada’s practice was the redefinition of authorship and originality. Marcel Duchamp’s readymades demonstrated that the act of selection and context-setting could be more significant than hand-crafted skill. Poets and visual artists alike experimented with chance operations – cutting up newspapers, drawing slips of paper from hats – to strip away ego and allow randomness to dictate form. Collage and photomontage became critical tools, enabling artists like Hannah Höch and Raoul Hausmann to repurpose mass-media images into biting social critique. Typography was treated as a visual medium in itself, with erratic layouts and jarring contrasts breaking the rules of conventional design to convey urgency and irreverence.

Performance, too, was integral. The Cabaret Voltaire staged wild, participatory evenings in which masked dancers, nonsense poetry, and music collided in an atmosphere closer to ritual or provocation than polite entertainment. Dadaists issued manifestos that alternated between bombastic declarations and self-mockery, undermining the authority of their own statements in real time. This refusal to settle into a single style or philosophy made Dada less a movement with fixed boundaries than a network of tactics – an evolving, self-contradictory method for questioning every assumption about what art could be and who it was for.

Cabaret Voltaire, Zurich (1916) – The Birthplace of Cultural Sabotage

At the Cabaret Voltaire, the line between art and event vanished. Hugo Ball’s famous “magical bishop” performance, reciting phonetic poems like Karawane, embodied Dada’s credo: language stripped of sense yet brimming with rhythm and ritual. Tristan Tzara mixed Balkan folk rhythms with jazz, masks, and chants, while Sophie Taeuber-Arp’s abstract dances and marionettes bridged theatre and visual art.

These nights were chaotic laboratories. The cabaret elevated ephemera – flyers, costumes, impromptu sketches – into equal status with painting or sculpture. It created a model of collaborative, process-based authorship that valued energy and disruption over permanence.

Marcel Duchamp’s Fountain (1917) — The Readymade Revolution

Duchamp’s submission of a porcelain urinal signed “R. Mutt” to an “open” exhibition exposed the hidden rules of the art world. By presenting a common object as sculpture, he revealed that meaning depends not on craft but on context, intention, and reception.

This strategy didn’t abandon creativity; it redefined it. The readymade anticipated conceptual art, Pop’s embrace of the commodity, institutional critique, and even debates about digital authorship. Fountain showed that the act of naming could be as radical as the act of making

“I was interested in ideas, not merely in visual products.”

Marcel Duchamp

Berlin Photomontage – Höch, Heartfield, Hausmann

Berlin Dada turned mass media into a political scalpel. Hannah Höch’s Cut with the Kitchen Knife Dada Through the Last Weimar Beer-Belly Cultural Epoch of Germany (1919–20) is a whirlwind of politicians, performers, and machine parts – feminist critique and political satire in one.

John Heartfield’s later anti-Nazi works – Hitler swallowing coins, the swastika fuelled by industrialists – proved that montage could be an urgent political weapon. Raoul Hausmann’s mechanomorphic figures turned people into machines, a bitter commentary on a society numbed by war and industry.

Dada’s Afterlives: Why It Still Matters

Conceptual Art’s Foundation. Dada shifted the focus from physical craft to the primacy of ideas, paving the way for artists like Joseph Kosuth, Yoko Ono, and Sol LeWitt. Their works echo Duchamp’s lesson: the artwork exists as much in the concept as in the object.

Institutional Critique and Performance. The Guerrilla Girls’ feminist interventions, Andrea Fraser’s satirical gallery tours, and Ai Weiwei’s politically charged gestures all draw from Dada’s use of performance as both cultural critique and public spectacle. These methods show how art can function as civic intervention, not merely decoration.

Appropriation, Remix, and Meme Culture. Today’s internet culture – memes, GIF mashups, TikTok remixes – operates with the same montage logic Dada pioneered. Like Berlin photomontage, these practices recombine existing material into commentary, often humorous, often political. Dada anticipated remix culture long before digital networks existed.

Graphic Design and Typography. Dada’s bold experiments with type, asymmetry, and collage layout influenced punk zines, editorial design, and experimental publications. Their disruption of the printed page liberated typography from strict grids, allowing it to convey emotion, tension, and critique.

Activism and Tactical Media. Groups like The Yes Men, Extinction Rebellion, and Pussy Riot employ stunts, parody and absurdity to challenge authority. These strategies directly descend from Dada’s belief in art as civil disobedience.

Post-Internet and AI Art. Artists using AI prompts, generative code, and data remixing enact the same questions Dada asked: What makes something art? Who decides? Where does authorship reside when replication is inevitable? Dada’s tools remain surprisingly effective in the 21st century.

Dada as a Method, Not a Museum Piece

Dada was never just a cluster of artworks; it was a way of thinking that converted disillusion into invention. By treating language as noise, objects as propositions, and exhibitions as provocations, Dada made art agile – capable of infiltrating cabarets, magazines, streets, and, eventually, institutions.

Its refusal of solemnity was not nihilism but a wager that laughter, sabotage and play might short-circuit violence and hypocrisy. A century on, Dada remains less a historical style than a living method: when culture ossifies, Dada asks us to cut it up and start again.

“Dada was not a school of artists but an alarm signal.”

Hans Richter

Browse 1000’s of Books in Our PromisesBooks Bookshop

Discover more from PEN vs SWORD

Subscribe to get the latest posts sent to your email.

What do you think?