Feminist Art From Inception to Today

The Feminist Art Movement

In tandem with our re-OpenLab ‘Architextures’ music series hosted by Francesca, here we look at The Feminist Art movement emerged in the late 1960s and 1970s in response to the exclusion of women from mainstream art institutions and art history. It was not just a call for inclusion but a radical rethinking of art, who makes it, and how it is valued. Feminist artists sought to challenge the traditional narratives of art history that had largely been shaped by men, for men, and often represented women as passive subjects. They aimed to create art that addressed the experiences, concerns, and perspectives of women, bringing visibility to issues such as gender inequality, reproductive rights, and the representation of the female body.

Table of Contents

*All book images suggest books that offer in-depth insights into the history, design philosophy, and impact of Brutalism and all book images Open a New tab to our Bookshop.

**If you buy books linked to our site, we get 10% commission from Bookshop.org, whose fees support independent bookshops.

Creating Spaces, Exhibitions and Dialogues

Initially, the movement was closely tied to the broader feminist movement of the 1960s and 1970s, which fought for equal rights in the workplace, education, and politics. In the art world, women were often marginalized or overlooked, with few exhibitions featuring their work and fewer galleries willing to represent them. Feminist artists challenged the male-dominated structures of the art world, creating their own spaces, exhibitions, and dialogues. The movement also emphasized collaborative and collective art-making practices, focusing on shared experiences and communal efforts rather than individual artistic genius, which had long been a male-dominated concept.

Historical Context and Early Challenges

The inception of the Feminist Art movement can be traced back to a few pivotal moments in the 1960s and early 1970s. In 1971, the art critic Linda Nochlin published her ground-breaking essay, Why Have There Been No Great Women Artists?, which exposed the structural barriers that had kept women out of art history. Nochlin argued that women had been systematically excluded from art education and the opportunities necessary to develop their craft, making it impossible for them to achieve the same recognition as their male counterparts.

Feminist Art Program

Another key moment came with the foundation of the Feminist Art Program at the California Institute of the Arts (CalArts) in 1970, created by artists Judy Chicago and Miriam Schapiro. This program was one of the first to prioritize the experiences of women in art-making and art education, and it led to the creation of one of the most iconic works of the movement, Womanhouse (1972). A collaborative installation in a dilapidated mansion, Womanhouse featured works that explored traditional roles of women in domestic spaces, offering a powerful critique of how women’s labour and experiences had been confined and overlooked.

“Feminist Art is not some tiny niche. It is, and always has been, the forefront of art-making.”

Judy Chicago

Momentum Through Grassroots Efforts

In the early years, Feminist Art was often dismissed by critics and institutions alike, seen as too political or didactic to be taken seriously as “real” art. Despite these challenges, the movement gained momentum through grassroots efforts, organizing exhibitions, founding feminist art publications, and establishing alternative art spaces such as A.I.R. Gallery in New York, the first cooperative gallery for women artists. Feminist artists used both traditional media and new, experimental forms like performance, video, and installation to address topics ranging from body politics to sexual identity to motherhood.

Judy Chicago and The Dinner Party

One of the most significant examples of the Feminist Art movement is Judy Chicago’s monumental installation, The Dinner Party (1974–79). The work is a symbolic history of women in Western civilization, presented as a triangular banquet table with 39 place settings, each one dedicated to an important woman in history or mythology. Each place setting features a hand-painted ceramic plate, often resembling a butterfly or a vulva, which serves as a symbol of female empowerment and creativity. The table itself is set on a floor inscribed with the names of 999 additional women, further emphasizing the long history of female contributions that have been systematically erased from historical records.

An Iconic Piece of Feminist Art

The Dinner Party was revolutionary for several reasons. It not only brought visibility to women’s achievements but also challenged traditional notions of “high art” by incorporating crafts such as needlework and ceramics, which had long been dismissed as “women’s work” and therefore not considered part of the fine arts. Chicago’s work also faced criticism, both from conservative voices who found it too provocative and from some feminists who felt it essentialised women’s experiences by focusing heavily on the female body. Nevertheless, The Dinner Party became an iconic piece of feminist art and remains a cornerstone of feminist art history today, housed at the Brooklyn Museum’s Elizabeth A. Sackler Center for Feminist Art.

“Our art is political. It questions the system, it demands change.”

Guerrilla Girls

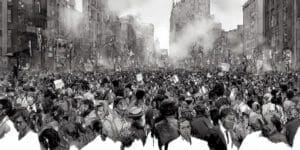

Guerrilla Girls and the Fight for Representation

In the 1980s, the Guerrilla Girls—a group of anonymous feminist artists who wore gorilla masks—took the fight for gender equality in the art world to new heights with their guerrilla tactics. The group formed in 1985 in response to an exhibition at the Museum of Modern Art in New York, which featured 165 artists, only 13 of whom were women. Outraged by this imbalance, the Guerrilla Girls launched a campaign of public art that exposed gender and racial inequalities in the art world, using posters, billboards, and other forms of media to call out institutions for their lack of diversity.

Humour, Statistics and Confrontational Imagery

One of their most famous posters, from 1989, asks, “Do women have to be naked to get into the Met Museum?” It highlights the fact that while women’s bodies were frequently represented in the museum’s collections, only a small percentage of the artists on display were women. The Guerrilla Girls’ combination of humour, statistics, and confrontational imagery made their message accessible and impossible to ignore. They not only criticized the exclusion of women but also called attention to the underrepresentation of artists of colour, expanding the conversation to include intersecting issues of race and class.

The Guerrilla Girls remain active today, continuing to challenge the art world’s power structures. Their work has broadened the scope of feminist art activism and has inspired new generations of artists and activists to question the status quo and demand a more inclusive and equitable art world.

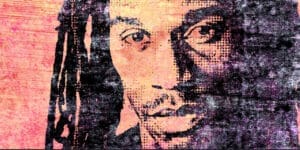

Ana Mendieta and Earth-Body Art

Ana Mendieta, a Cuban-American artist, is another powerful figure within the Feminist Art movement, known for her “earth-body” works that combine performance, sculpture, and land art. Her work often explored themes of identity, exile, and the connection between the body and nature. One of her most famous series is Silueta, created between 1973 and 1980, in which she used her own body to create temporary earthworks, leaving behind silhouettes or imprints in natural environments such as beaches, forests, and fields. Mendieta would use natural materials like mud, leaves, and blood to create these works, which were often ephemeral, lasting only a short time before being reclaimed by the earth.

Mendieta’s work reflects a deep engagement with issues of displacement and identity, stemming from her own experience as a refugee who fled Cuba as a child. Her use of her body as both subject and medium was ground-breaking, as it connected the personal and political in ways that challenged the male-dominated art world of the time. Mendieta’s work has been interpreted as a feminist reclaiming of the female body, which has historically been objectified in art, but in her hands became a site of power and transformation. Although her life was tragically cut short in 1985, her influence on feminist art continues to be profound, and her work has been increasingly recognized in retrospectives and exhibitions worldwide.

Contemporary Feminist Art and Its Future

Feminist Art has continued to evolve, reflecting the changing landscape of both feminism and the art world. In the 1990s, the third wave of feminism brought a more inclusive, intersectional approach to feminist art, focusing not only on gender but also on race, sexuality, and class. Artists like Kara Walker, Cindy Sherman, and Barbara Kruger explored these themes, often using irony and pastiche to critique representations of women and power structures in media and culture.

New Media and Digital Technologies

In the 21st century, the feminist art movement has intersected with new media and digital technologies, enabling a broader and more diverse range of voices to participate. Social media platforms like Instagram have become powerful tools for feminist artists to share their work, build communities, and engage in activism. Artists such as Tschabalala Self and Mickalene Thomas are continuing to push the boundaries of feminist art, exploring issues of race, gender, and sexuality in bold, innovative ways.

A Powerful Force for Social Change.

While the art world has made progress in terms of gender equity, significant challenges remain. Women artists, particularly women of colour, continue to be underrepresented in galleries and museums. However, the rise of feminist art collectives, online platforms, and independent spaces dedicated to showcasing marginalized voices offers hope for a more inclusive future. The ongoing relevance of Feminist Art lies in its ability to adapt and respond to new challenges, ensuring that it remains a powerful force for social change.

Contributing to Art History and Feminist Discourse

The Feminist Art movement has reshaped the way we think about art and who gets to make it. From its roots in the 1960s and 1970s to its continued relevance today, feminist artists have challenged the exclusionary practices of the art world, created spaces for women’s voices, and used their work to address broader social and political issues.

Whether through the monumental impact of Judy Chicago’s The Dinner Party, the provocative activism of the Guerrilla Girls, or the deeply personal, earth-bound work of Ana Mendieta, Feminist Art has made lasting contributions to both art history and feminist discourse. As the movement continues to evolve, it remains a vital space for exploring questions of identity, representation and power, ensuring that the voices of women and all marginalized groups, will continue to shape the future of art.

“I use my body as a means to create art that is ephemeral, but that speaks to the permanence of identity and belonging.”

Ana Mendieta

Leave a Comment