Alexander Calder, architecture, architextures, bauhaus, Carlos Cruz-Diez, cybernetic, Francesca, futurist, Giacomo Balla, GRAV, interactions, Jean Tinguely, Jesús Rafael Soto, kinetic art, kineticism, kinetics, László Moholy-Nagy, Light-Space Modulator, motion, Nicolas Schöffer, Olafur Eliasson, Op Art, sculpture, spatiodynamic art, technology, Umberto Boccioni

Kineticism: Movement in Art and Architecture

Kinetic Art as a Global Movement

In tandem with our re-OpenLab ‘Architextures’ music series, we look at Kineticism, or Kinetic Art, is a dynamic movement that explores the perception of motion in visual and sculptural art. Born in the early 20th century, it challenged static conventions, emphasizing movement as a central component of artistic experience. With roots in both art and technology, Kinetic Art uses physical or optical motion to engage viewers, making them participants in the artwork’s experience.

The philosophy behind Kineticism goes beyond creating static images or forms – it invites interaction, relying on the perception of movement to generate meaning. Over time, this radical approach to art has influenced a wide range of artistic expressions, from sculptures that physically move to paintings that create the illusion of motion.

Table of Contents

“The role of the artist is to make kinetic art speak, to make it move the viewer, both emotionally and physically.”

Jean Tinguely

Origins and Early Development: A Futurist Prelude

The seeds of Kineticism were sown in the early 20th century by the Futurists, who celebrated the dynamism of the modern world. Artists like Umberto Boccioni and Giacomo Balla embraced speed, motion, and the energy of machines in their work. Futurism reflected the industrial age’s fascination with technology, and Kinetic Art would later build upon this foundation by making movement itself an essential aspect of the artwork. As the modern world moved faster, the desire to capture this motion in art grew stronger.

However, Kineticism truly began to take shape as a distinct movement in the 1920s and 1930s with the Bauhaus school in Germany. Artists like László Moholy-Nagy experimented with light, movement, and industrial materials, emphasizing the importance of integrating technology and art. Moholy-Nagy’s Light-Space Modulator (1922–1930) is considered one of the first kinetic sculptures, using light and shadow to create dynamic visual effects. The Bauhaus’ embrace of interdisciplinary practices laid the groundwork for a new kind of art—one where technology, physics, and artistic expression intersected to create works that were not just viewed but experienced.

“My mobiles are not just sculptures; they are a ballet of movement and balance.”

Alexander Calder

Post-War Expansion: Kinetic Art as a Global Movement

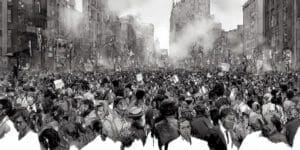

After World War II, Kineticism expanded into a global phenomenon, with artists from different regions contributing to the movement. The post-war era was marked by rapid technological advancements, and Kinetic Art reflected a world that was becoming increasingly mechanized and interconnected. The movement gained prominence in Europe in the 1950s and 1960s, particularly in France, where a group of artists known as Groupe de Recherche d’Art Visuel (GRAV) began exploring the optical and physical effects of movement. GRAV sought to create participatory art that engaged viewers in a direct and active way, often involving them in the manipulation of the artwork itself.

In Latin America, artists such as Jesús Rafael Soto and Carlos Cruz-Diez explored optical illusions and the relationship between the viewer and the artwork. Their work emphasized how movement could be perceived without the physical motion of the artwork itself, relying on the interaction between light, color, and the observer’s perspective. This approach became known as Op Art (Optical Art), closely related to Kineticism, and it broadened the movement’s scope by including perceptual phenomena in addition to mechanical motion.

*All Book Images Open a New tab to our Bookshop

**If you buy books linked to our site, we get 10% commission from Bookshop.org, whose fees support independent bookshops.

Kineticism in the Age of Technology

As the 20th century progressed, Kineticism evolved in tandem with advancements in technology, particularly with the rise of electronics and digital media. Artists like Jean Tinguely took Kinetic Art to new heights with mechanical sculptures that physically moved, often powered by motors. His famous work Homage to New York (1960), a self-destructing machine, embodied the intersection of art, motion, and technology, questioning the role of machines in modern life while making motion the central focus of his work.

During this period, kinetic sculptures began to proliferate in public spaces, emphasizing interactivity and participation. Alexander Calder’s mobile sculptures, which shifted with air currents, became iconic examples of Kineticism in the 20th century. Calder’s work, which balanced motion with aesthetic harmony, demonstrated how movement could evoke playfulness and wonder. His delicate mobiles, such as Lobster Trap and Fish Tail (1939), seemed to defy gravity, embodying both artistic grace and scientific curiosity.

Jean Tinguely’s Homage to New York (1960)

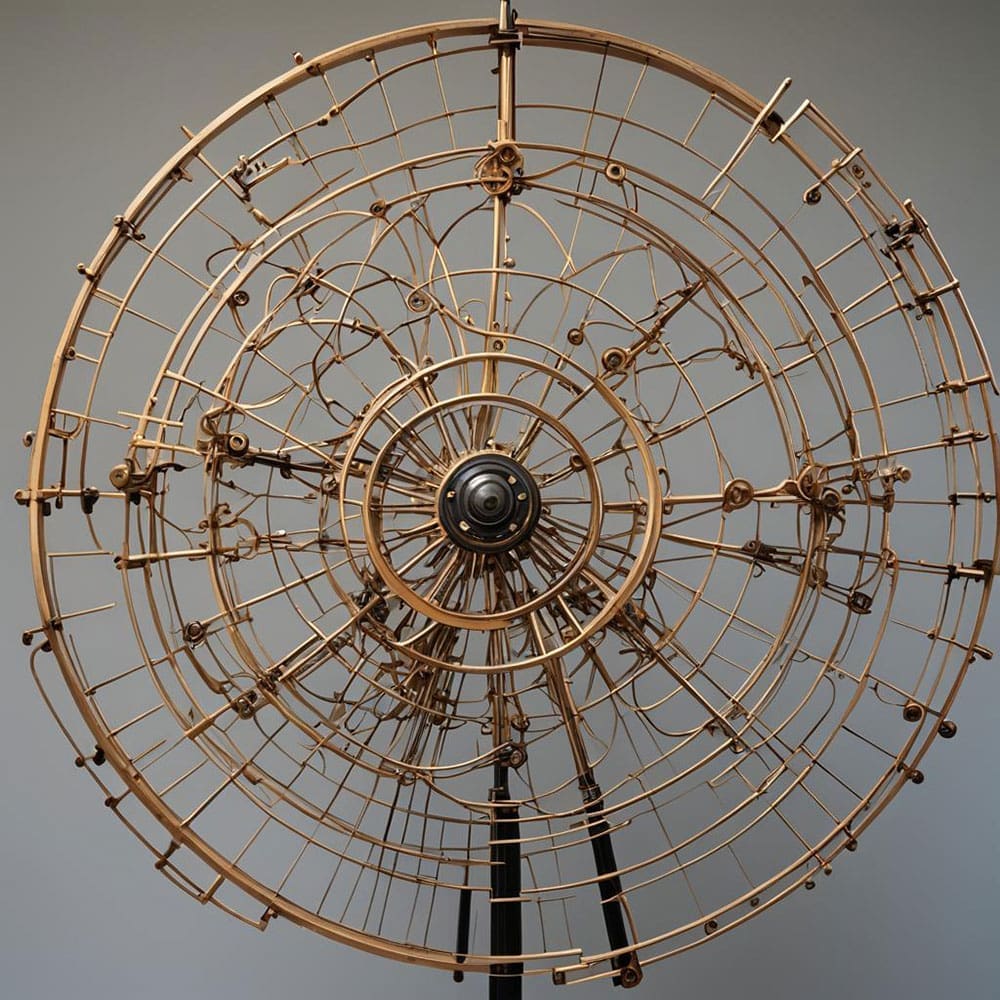

Jean Tinguely’s Homage to New York stands as one of the most famous and audacious kinetic artworks ever created. This massive, self-destructing machine was designed to break down and destroy itself during its performance at the Museum of Modern Art in New York. Made from found materials, scrap metal, and mechanical parts, the sculpture was an elaborate contraption that moved, made noise, and eventually fell apart in a chaotic spectacle. Tinguely was fascinated by the idea of art as a fleeting experience, and Homage to New York captured this ephemeral quality, forcing viewers to confront the temporality of both machines and art.

The destruction of Homage to New York was not just a technical feat but a philosophical statement about the relationship between humans and machines in the modern world. Tinguely’s work challenged the viewer to see art not as a static object but as an experience bound to the passage of time. His kinetic sculptures often employed humor and absurdity, critiquing the mechanization of society while celebrating the unpredictable beauty of motion. Homage to New York is a prime example of how Kinetic Art could engage audiences in novel ways, combining performance, mechanics, and philosophy into a singular artistic event.

Alexander Calder’s Mobiles (1930s onwards)

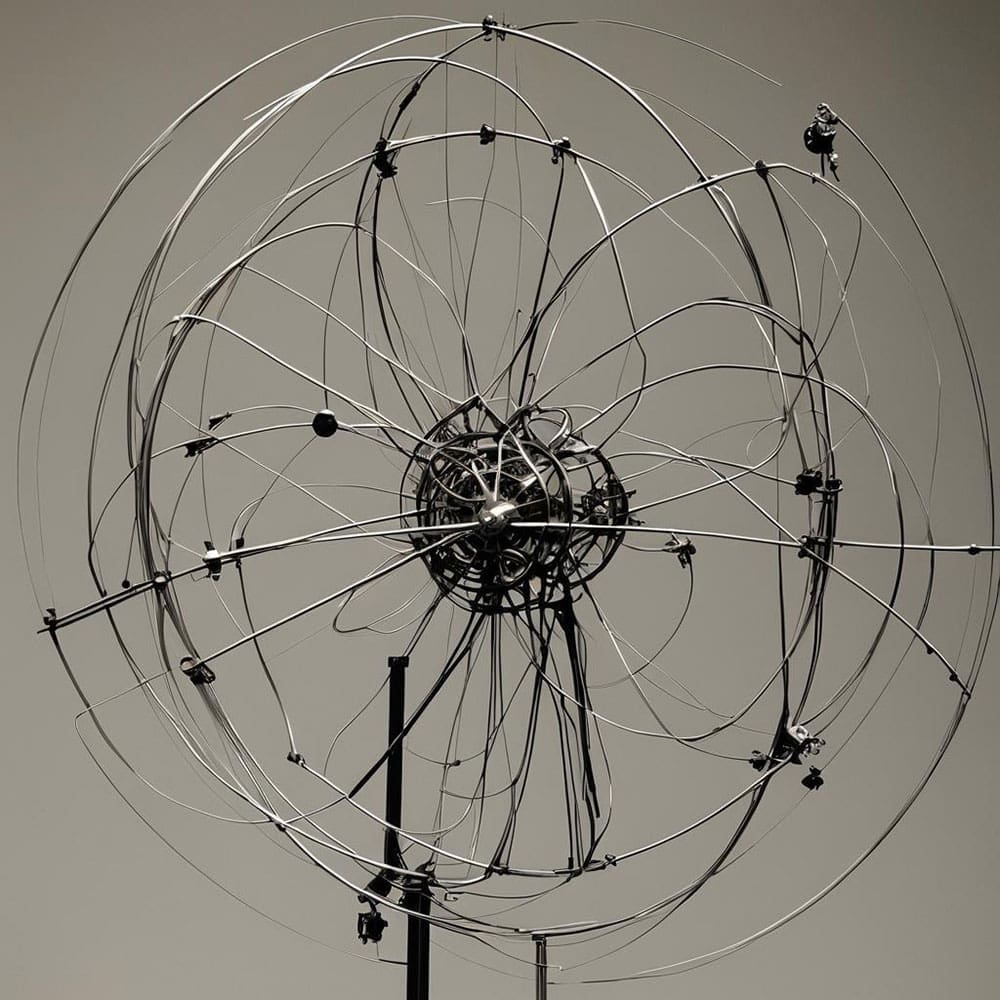

Alexander Calder revolutionized sculpture with his kinetic mobiles, which transformed static objects into dynamic artworks moved by air currents. Calder’s mobiles consist of delicately balanced shapes that are suspended in space, moving unpredictably in response to their environment. One of his most famous works, Lobster Trap and Fish Tail (1939), is a large-scale mobile that hangs in the Museum of Modern Art. It is composed of thin metal arms connected by wires, with abstract forms that sway and rotate, casting ever-changing shadows on the surrounding walls.

Calder’s mobiles are a unique example of how movement can introduce an element of spontaneity into art. Rather than relying on motors or mechanical devices, Calder used natural forces like wind or air to animate his creations. The seemingly random movements of his mobiles have a serene and mesmerizing quality, inviting the viewer to observe the subtle interplay of form, space, and time. Calder’s work represents a gentler, more meditative side of Kineticism, one that highlights the beauty of natural motion and the harmony between art and environment.

Nicolas Schöffer’s CYSP 1 (1956)

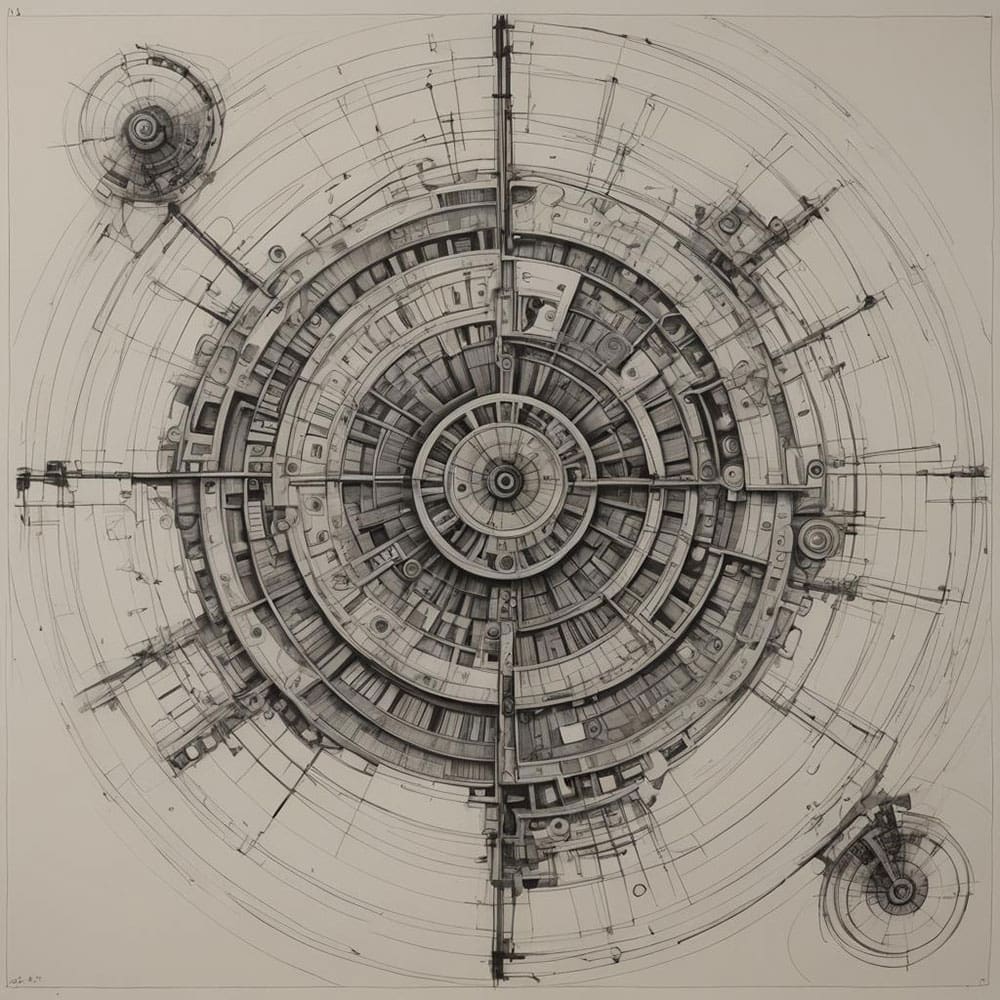

Nicolas Schöffer was a Hungarian-French artist who pioneered the use of cybernetics in Kinetic Art, blending art and technology in groundbreaking ways. His sculpture CYSP 1 (1956) was one of the first cybernetic sculptures, a moving artwork equipped with electronic sensors that responded to its surroundings. The sculpture could move autonomously, reacting to environmental stimuli such as light, sound, and motion. Schöffer’s work anticipated the development of interactive and responsive artworks that have become common in contemporary art today.

CYSP 1 exemplified Schöffer’s belief that art should evolve in response to its environment, not just remain a static creation. His concept of “spatiodynamic” art proposed that movement should not only be physical but also involve the interaction between the artwork and its space. The piece could “decide” its movements based on the input it received from its sensors, creating a dialogue between the machine, its environment, and the viewer. Schöffer’s exploration of technology in art laid the foundation for interactive and kinetic installations that continue to push the boundaries of art in the digital age.

Kineticism Today: A Lasting Influence

Kineticism remains a vital influence on contemporary art, architecture, and design. The movement’s emphasis on motion and viewer interaction has inspired a new generation of artists who use digital technologies, robotics, and artificial intelligence to create dynamic works. Today, Kinetic Art often overlaps with fields like interactive media, virtual reality, and digital installations, pushing the boundaries of what art can do and how it can be experienced.

Modern kinetic artists frequently use digital and mechanical systems to engage viewers in immersive experiences. For example, light-based installations by artists like Olafur Eliasson and interactive exhibits by studios like TeamLab have brought the kinetic principles of motion and viewer engagement into the 21st century. These works highlight how Kineticism continues to evolve, integrating new technologies to further explore the possibilities of movement in art.

“Kinetic art is not only about movement; it is about engaging the senses and the mind, creating a new experience each time it is viewed.”

Nicolas Schöffer

The Future of Kineticism

As technology continues to advance, the future of Kineticism looks bright. Artists are increasingly incorporating robotics, artificial intelligence, and algorithms into their works, creating pieces that can learn, adapt, and change over time. The integration of kinetic principles into architecture is also gaining momentum, with dynamic buildings and responsive facades that move and adapt to environmental conditions, enhancing both aesthetic appeal and energy efficiency.

In the coming decades, Kinetic Art is likely to merge further with science and technology, challenging the boundaries between art, design, and engineering. The interactive, participatory nature of Kineticism offers exciting possibilities for creating spaces that engage, inspire, and evolve, much like the early kinetic sculptures sought to do. As we move into an era of smart cities and responsive environments, Kineticism will likely play a key role in shaping how we experience both art and the world around us.

Transforming the way we Think About and Experience Art

Kineticism with its emphasis on movement and viewer participation, has transformed the way we think about and experience art. From its early roots in the Futurist and Bauhaus movements to its current integration with advanced technologies, Kinetic Art has continually pushed the boundaries of artistic expression. Artists like Jean Tinguely, Alexander Calder, and Nicolas Schöffer pioneered a new form of art that invites interaction, movement, and change, making Kineticism an enduring and dynamic force in the art world. As technology advances, Kineticism will continue to evolve, shaping the future of art, architecture, and design in ways we are only beginning to imagine.

Browse 1000’s of Books in Our PromisesBooks Bookshop

More

Tag

Alexander Calder architecture architextures bauhaus Carlos Cruz-Diez cybernetic Francesca futurist Giacomo Balla GRAV interactions Jean Tinguely Jesús Rafael Soto kinetic art kineticism kinetics László Moholy-Nagy Light-Space Modulator motion Nicolas Schöffer Olafur Eliasson Op Art sculpture spatiodynamic art technology Umberto Boccioni

Leave a Comment