The Metabolist Movement

Radical Architecture and Urban Design

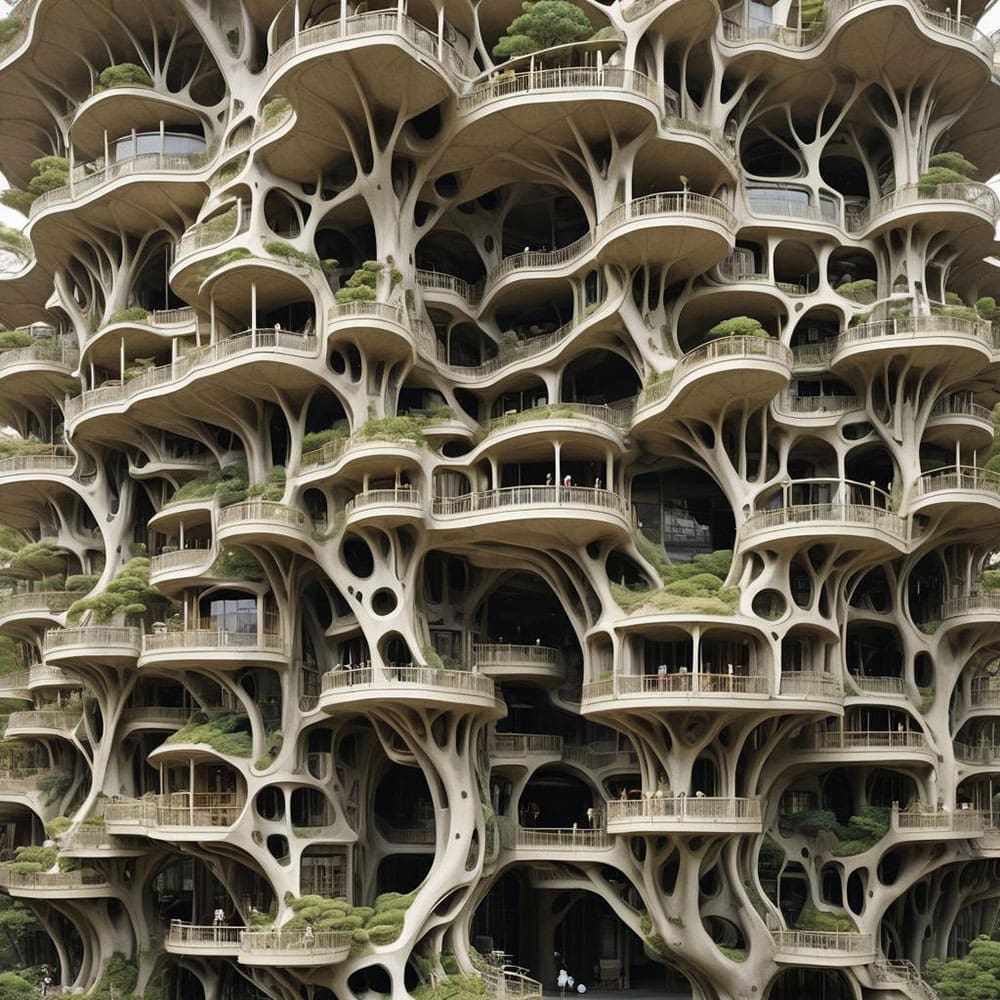

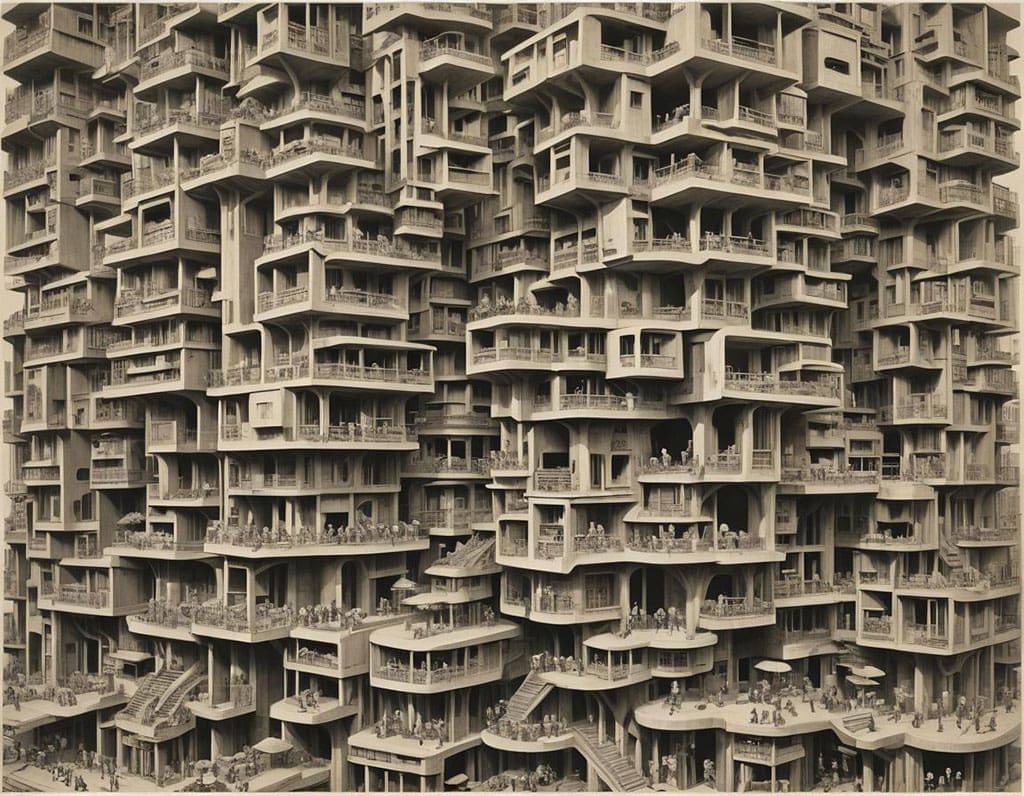

In tandem with our re-OpenLab ‘Architextures’ music series, we look at the Metabolist movement, one of the most radical architectural and urban design philosophies to have emerged in the 20th century. Born in post-war Japan, it is marked by its futuristic approach to design, one that merges biology, growth, and flexibility with human habitats. The Metabolist philosophy advocates for a continuous regeneration of architectural structures, much like biological processes, with buildings designed to evolve, grow, and adapt with time. This visionary approach to urban planning and architecture would inspire architects, designers, and urbanists worldwide, cementing its importance in the history of modern architecture.

Table of Contents

“The human race should become a new species - one that makes cities that are symbiotic with nature and with our own changing needs.”

Kiyonori Kikutake

Origins and Philosophy: A Post-War Vision

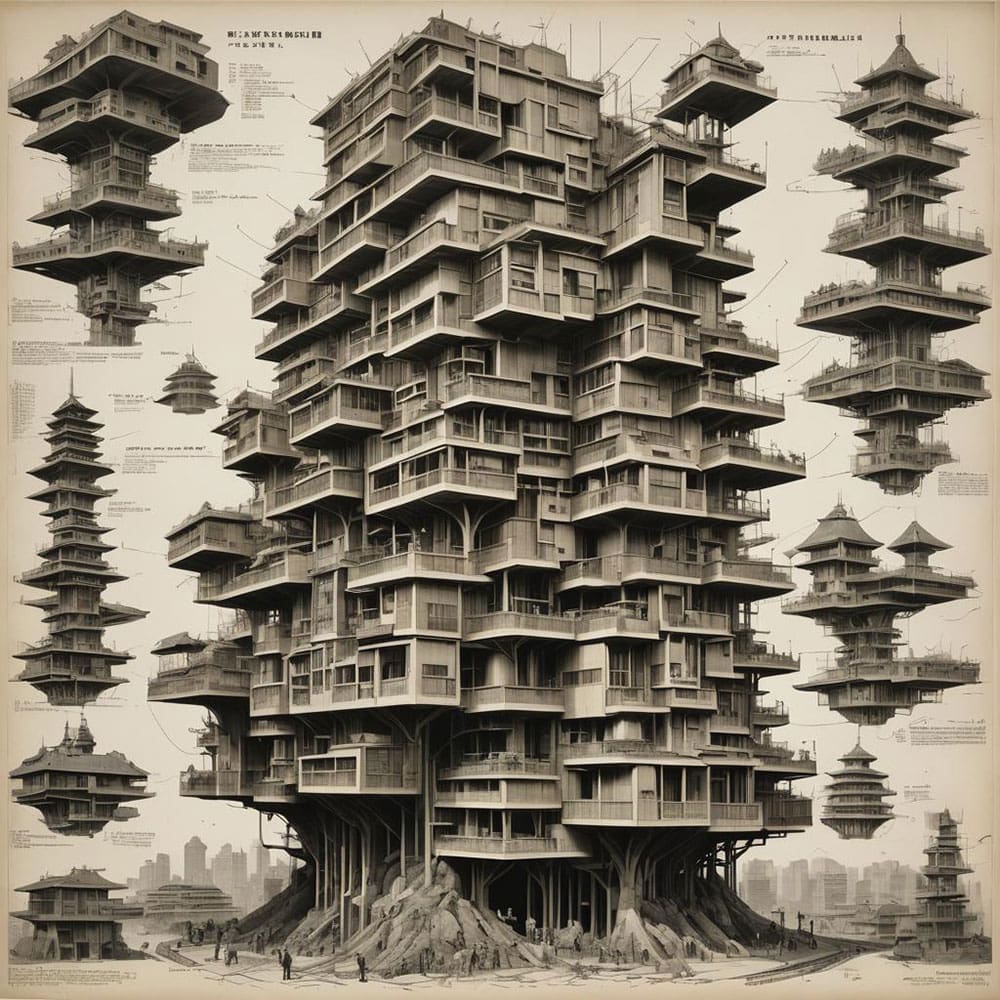

The Metabolist movement began in 1960 in Tokyo, Japan, following the devastation of World War II. Japan was in the process of rebuilding its cities and society, and architects and urban planners sought a new vision for this post-war era. The founding figures of the movement included a group of young architects and designers—Kiyonori Kikutake, Kisho Kurokawa, and Fumihiko Maki, along with critic and writer Noboru Kawazoe. The group officially debuted during the 1960 World Design Conference in Tokyo with their manifesto titled “Metabolism 1960: The Proposals for a New Urbanism.”

Their manifesto proposed cities and buildings that could grow and change with time, much like living organisms. Kisho Kurokawa, a key member, would later define Metabolism as the idea of “change and growth through phases of development,” stressing the importance of adaptability and impermanence in urban development. The focus on flexibility and organic growth was in sharp contrast to the static, monumental architectural styles of earlier decades. In their vision, buildings were not meant to be permanent fixtures but parts of larger systems capable of being expanded, contracted, or replaced based on the needs of society.

“The human race should become a new species – one that makes cities that are symbiotic with nature and with our own changing needs.”

Kisho Kurokawa

Growth and Influence in Japan

The Metabolists sought to respond to Japan’s rapid post-war modernization and urbanization. Tokyo, in particular, was undergoing a population boom, and the country was transitioning from an agricultural to an industrialized society. The group believed that this transformation required an innovative approach to urban planning and architecture. Their designs incorporated modular structures, floating cities, and mega structures that could grow and evolve over time, adapting to the dynamic needs of society.

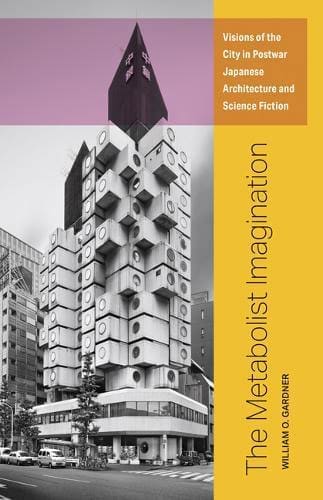

One of the Metabolists’ most famous projects is Kisho Kurokawa’s Nakagin Capsule Tower in Tokyo, completed in 1972. This building, composed of modular, prefabricated capsules that could be attached or removed, was emblematic of the movement’s principles. The idea was that individual living spaces could be replaced as needed, ensuring the building’s longevity without requiring a complete demolition. Although it was never expanded as originally envisioned, the Nakagin Capsule Tower remains one of the most iconic examples of the Metabolist philosophy.

*All Book Images Open a New tab to our Bookshop

**If you buy books linked to our site, we get 10% commission from Bookshop.org, whose fees support independent bookshops.

Nakagin Capsule Tower by Kisho Kurokawa (1972)

The Nakagin Capsule Tower is perhaps the most famous realization of the Metabolist ideals. Located in the bustling Ginza district of Tokyo, the building consists of two concrete towers onto which individual capsule units are attached. Each unit is a small, prefabricated room, equipped with everything necessary for urban living in a compact space. What made this project so unique was its potential for regeneration. Each capsule was designed to be removable and replaceable, allowing the structure to adapt over time, responding to changing demands and technological advancements.

While the building has faced demolition threats due to its deterioration, many architectural enthusiasts and historians advocate for its preservation as an iconic representation of Metabolism. The Nakagin Capsule Tower serves as a case study in the success and limitations of the Metabolist vision. It demonstrated the potential for modularity and adaptability, though it also revealed the challenges of maintaining such structures, particularly in a city like Tokyo, where land and resources are highly coveted. Nonetheless, it remains a symbol of the bold ambitions of post-war Japan.

Marine City by Kiyonori Kikutake (1963 proposal)

Kikutake’s proposal for Marine City is another hallmark of the Metabolist movement. Though it was never fully realized, the design envisioned a floating city on the sea that could expand and grow as needed. The core concept was a vast, floating platform anchored to the ocean floor, which would serve as the basis for further expansion. Residential, commercial, and industrial zones could be added modularly, in a way that resembled biological growth.

Marine City’s significance lies in its response to Japan’s land shortage and its innovative use of technology to reimagine urban living spaces. The project also emphasized sustainability—well before the term gained its contemporary relevance—by proposing a floating city as a means to mitigate the increasing pressures of urbanization on Japan’s limited land resources. The design of Marine City remains a visionary example of urban design, blending futuristic technology, environmental awareness, and an organic growth model.

Shizuoka Press and Broadcasting Center by Kenzo Tange (1967)

Kenzo Tange, although not an official member of the Metabolist group, was a major influence on its development. His Shizuoka Press and Broadcasting Center, built in 1967, exemplifies many of the Metabolist ideals. The building consists of a central tower, with cantilevered office modules that branch out from the core like leaves from a stem. Each module could theoretically be expanded or replaced without disturbing the rest of the structure, embodying the idea of architectural growth and change over time.

This design became a key inspiration for future architects in the Metabolist movement. Tange’s work also represented a bridge between traditional Japanese architectural principles and modernist, futuristic ideals. His Shizuoka Press building became a prototype for flexible, modular construction in dense urban environments. Though the building did not have the biological, growth-oriented adaptability envisioned by Metabolists, it served as a tangible example of what their philosophy could achieve in practice.

The Metabolist Movement Today

While the Metabolist movement was primarily active in the 1960s and 1970s, its influence is still felt today in both architectural theory and practice. Modern-day concepts of sustainability, modularity, and adaptable urban design are directly tied to the principles laid out by the Metabolists. For example, the growing focus on prefabricated and flexible housing systems in response to urban density challenges echoes the movement’s core philosophy.

However, some critics argue that the movement’s ideas were too utopian and failed to account for practical concerns, such as maintenance costs and political constraints. The Nakagin Capsule Tower, though iconic, faces possible demolition due to the difficulty of maintaining its modular structure. Despite these challenges, the Metabolist vision has found new life in contemporary discussions about the future of cities in the face of climate change, population growth, and technological advancement.

The Future of Metabolist Ideals

The Metabolist movement remains relevant as architects and urban planners face unprecedented challenges in the 21st century. As cities around the world struggle with issues like overpopulation, environmental degradation, and resource scarcity, the need for adaptable, sustainable urban solutions has never been more urgent. The Metabolists’ vision of cities that grow and change organically offers valuable lessons for the future.

As technologies such as 3D printing, smart cities, and modular construction advance, the potential for realizing Metabolist ideals becomes increasingly feasible. Moreover, the movement’s focus on blending architecture with natural ecosystems resonates with the growing trend toward biophilic design—an approach that integrates natural elements into urban spaces. In this sense, the Metabolist vision is perhaps more relevant today than ever before, offering a blueprint for cities that can grow, adapt, and evolve in harmony with both technological and environmental change.

“We must not view architecture as something static; it must be flexible and dynamic, capable of continuous regeneration.”

Fumihiko Maki

Continuing to Inspire Innovation

The Metabolist movement, born out of post-war Japan’s desire for renewal and growth, offered a bold, futuristic vision of architecture and urban design that remains relevant today. While its most iconic projects, like Kisho Kurokawa’s Nakagin Capsule Tower and Kiyonori Kikutake’s Marine City, represented ambitious ideas of adaptability, modularity, and symbiosis with nature, the movement also encountered practical limitations. Yet, as cities today grapple with the challenges of sustainability, overpopulation, and environmental change, the Metabolist ideals of flexible, regenerative urban planning continue to inspire innovative solutions, reminding us of architecture’s potential to evolve alongside society.

Leave a Comment