The Sonic Dimensions of Contemporary Art

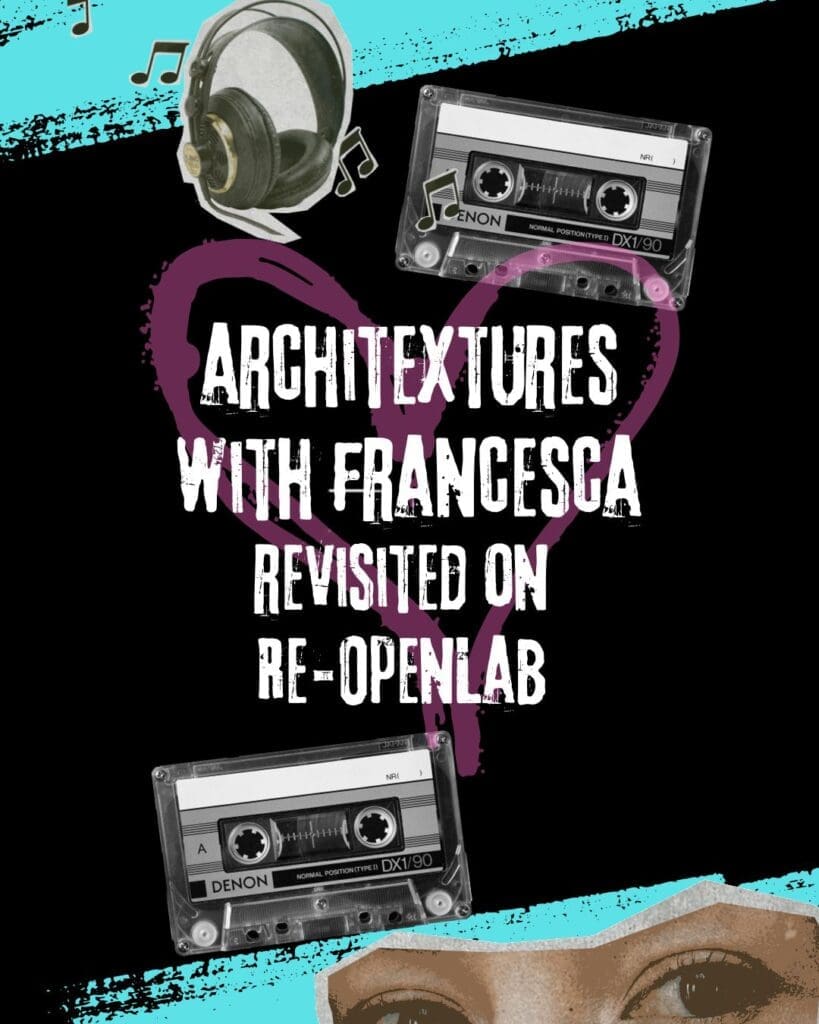

In tandem with our re-OpenLab ‘Architextures’ music series hosted by Francesca, here we look at a Sound Art, which is an interdisciplinary art form that places sound at the centre of artistic exploration. Unlike traditional music, which is typically structured and temporal, sound art emphasizes the spatial, physical, and conceptual properties of sound, often in combination with visual, architectural, or interactive elements.

Emerging in the mid-20th century, it challenged conventional notions of both music and visual art, creating immersive environments that engage audiences’ auditory senses in new ways. By foregrounding listening as an active, participatory experience, sound art encourages reflection on perception, space, and the relationship between human beings and their sonic environment.

All of our content is free to access. An independent magazine nonetheless requires investment, so if you take value from this article or any others, please consider sharing, subscribing to our mailing list or donating if you can. Your support is always gratefully received and will never be forgotten. To buy us a metaphorical coffee or two, please click this link.

Table of Contents

*All book images suggest books that offer in-depth insights into the history, design philosophy, and impact of Feminist Art and all book images Open a New tab to our Bookshop.

**If you buy books linked to our site, we get 10% commission from Bookshop.org, whose fees support independent bookshops.

Early Foundations and Avant-Garde Influences

The origins of sound art can be traced back to the early 20th century. Italian Futurist Luigi Russolo’s 1913 manifesto, L’arte dei rumori (The Art of Noises), argued that the industrial sounds of modern life should be embraced as musical material. Russolo built intonarumori, or noise-generating machines, to create performances incorporating machine and environmental sounds. These early experiments laid the groundwork for sound as an artistic medium rather than just a musical element.

In the 1950s and 1960s, composers such as John Cage expanded these ideas. Cage’s seminal work 4’33” (1952), a piece of silence punctuated only by ambient sounds, questioned the boundaries of music and art, emphasizing that all sounds – intentional or accidental – hold aesthetic value. This radical approach inspired a generation of artists to consider sound as a sculptural, spatial, and experiential phenomenon.

Development in the 1960s and 1970s

The 1960s and 1970s saw the emergence of sound art as a recognized field. Artists like Max Neuhaus and Alvin Lucier blurred lines between music, installation, and conceptual art. Neuhaus’s Times Square (1977) installed speakers beneath a grate in New York City, creating a continuous sound that transformed the perception of an urban environment. Lucier’s I Am Sitting in a Room (1970) explored room acoustics by re-recording speech repeatedly, allowing natural resonances to sculpt the sound into a new, evolving composition.

Institutional Recognition and Global Expansion

By the late 1970s, sound art began to be recognized in galleries and museums. Barbara London’s 1979 MoMA exhibition Sound Art highlighted the medium’s distinct position between visual art and music. Since then, sound art has flourished globally, adapting to digital technologies and emerging media, from interactive installations to immersive, sensor-driven environments. Today, it is celebrated as a vital field of contemporary art that challenges audiences to rethink the role of sound in experience and space.

The Defining Principles and Characteristics of Sound Art

Sound art is defined by its emphasis on sound as the primary medium, prioritizing the listener’s experience over conventional musical structure. Rather than relying on melody, harmony, or rhythm, sound artists manipulate acoustics, textures, and environments to create complex sonic landscapes. The medium explores how sound occupies and interacts with space, often incorporating found objects, mechanical devices, or electronic technology. By emphasizing subtle shifts in resonance, timbre, and spatial perception, sound art transforms listening into a focused, contemplative, and participatory act.

Equally important is sound art’s interdisciplinary and immersive nature. Works often integrate visual elements, architecture, or interactive components, transforming audiences into active participants. Many installations are site-specific, responding to the unique acoustics and spatial characteristics of a location, which makes each experience distinct. This approach challenges traditional divisions between music, visual art, and conceptual practice, positioning sound art as both a sensory and philosophical exploration of perception, environment, and the human experience.

“Sound is a medium that can be experienced directly and immediately.”

Max Neuhaus

Max Neuhaus – Times Square (1977)

Max Neuhaus’s Times Square is a landmark work in sound art. By placing speakers beneath a sidewalk grate in New York City, Neuhaus created a continuous, resonant tone that subtly shifted as pedestrians passed by. The work recontextualized the urban soundscape, transforming an ordinary city intersection into a site of contemplative auditory experience. Neuhaus’s work demonstrates how sound can alter perception of space and time, making everyday environments into artistic encounters.

Alvin Lucier – I Am Sitting in a Room (1970)

Alvin Lucier’s I Am Sitting in a Room explores the acoustical properties of physical space. Lucier recorded himself reading a text and then played the recording back into the room, re-recording each iteration. Over time, the resonant frequencies of the room transformed the speech into musical harmonics, turning language into pure sound. The piece highlights the interplay between sound, space, and perception, emphasizing the medium’s conceptual as well as auditory dimensions.

Janet Cardiff – The Forty Part Motet (2001)

Janet Cardiff’s The Forty Part Motet is an immersive installation featuring forty speakers arranged in a circular pattern, each playing a separate vocal track of a choral piece. Listeners are free to move among the speakers, experiencing the music from varying spatial perspectives. The installation not only reveals the subtleties of choral performance but also emphasizes sound’s spatial and relational qualities, immersing participants in a dynamic auditory environment.

“I am interested in the way sound behaves in a space.”

Alvin Lucier

Zimoun – Kinetic Sound Sculptures

Swiss artist Zimoun creates large-scale kinetic sound installations using simple mechanical systems such as motors, fans, and cardboard boxes. His works often involve hundreds of small elements generating repetitive, rhythmic sounds that create immersive, evolving soundscapes. Zimoun’s pieces exemplify how sound art can transform minimal materials into complex auditory experiences, highlighting the medium’s capacity for both physical and conceptual exploration.

Sound Art in Contemporary Culture

Integration with Technology – Contemporary sound artists increasingly employ digital tools, sensors, and interactive media. These technologies allow works to respond in real-time to audience movements or environmental changes, creating dynamic and participatory experiences. Virtual reality and immersive soundscapes extend the principles of sound art into new media, offering audiences entirely novel forms of auditory engagement.

Environmental and Political Engagement – Many contemporary practitioners use sound art to engage with environmental or political themes. Field recordings of urban or natural environments are manipulated to draw attention to climate change, noise pollution, or urban density. By foregrounding sound as both subject and medium, these works encourage audiences to reconsider their relationship with the world and the ecological or social systems that shape their experience.

Public and Site-Specific Installations – Sound art often thrives in public and site-specific contexts, transforming everyday spaces into interactive auditory environments. From parks and train stations to museums and galleries, installations engage passers-by directly, making art accessible and participatory. This approach reinforces sound art’s capacity to intervene in perception, creating ephemeral yet impactful experiences that merge life and art.

The Enduring Impact of Sound Art

Sound art remains a vital and evolving discipline in contemporary art, emphasizing perception, space, and auditory experience. Its focus on sound as a medium, combined with its interdisciplinary and immersive approach, challenges audiences to engage with the environment and reconsider the boundaries of music, art, and design.

From early Futurist experiments to contemporary digital installations, sound art continues to transform the way we experience the world, proving that listening can be as profound as seeing. As technology, space, and environmental consciousness evolve, sound art will remain a dynamic, exploratory medium, bridging art, science, and everyday experience.

“I want to create an experience that is immersive and transformative.”

Janet Cardiff

What do you think?