Zarina Zabrisky Interview

As she documents the war in Ukraine from frontline cities, Zarina Zabrisky doesn’t flinch, she moves through devastation with a fierce clarity – and an unshakeable faith in the power of human testimony.

Her latest work, Kherson: Human Safari, is a 72-minute descent into the underbelly of Russia’s invasion of Ukraine – told not through distant strategy or military hardware, but through the eyes and voices of survivors. From the first days of occupation to ongoing drone terror, Zabrisky traces how a city – and its people – resist erasure.

In this interview, she speaks to Pen vs Sword about the ethics of witnessing, the role of language in trauma and what it means to produce and direct this unique documentary.

Read this in depth interview with Zarina Zabrisky, soak up the reality of life in Kherson and then watch the film Kherson: Human Safari – there’s a link to it at the end of this in depth interview with Zarina Zabrisky.

Table of Contents

All of our content is free to access. An independent magazine nonetheless requires investment, so if you take value from this article or any others, please consider sharing, subscribing to our mailing list or donating if you can. Your support is always gratefully received and will never be forgotten. Buy us a metaphorical coffee or two – please click this link.

All Have Their Voices

Kherson: Human Safari is more than a documentary – it feels like a psychological record of occupation. What was the emotional weight of reporting in such charged territory?

The film is the collective story of the city, with the city becoming the main character – through the voices of its residents. And not just people – urban life is rich and intricate here. Animals, birds, trees and plants, the river – all have their voices, or, like in the case of the Dnipro River, the lack of voice, silence. You can’t come to the river, as death awaits on the other side.

The filmmakers become the medium, the recording device, the amplifier. It was critically important to me not to interfere and not to mix my own feelings into the story of Kherson. Many stories are unbearably hard – and many are inspiring and uplifting – but the side effects of getting these stories into the world are not something that I am interested in.

I am writing a book, and that would be more personal and will explore the role of a journalist in reporting. But this, probably, will be completed after the Victory. I feel that it is not important now, while our reporting can help save human lives and the existence of the country.

“Safari on people” was the exact Ukrainian phrase she used…

*All Book Images Open a New tab to our UK Bookshop

**If you buy books linked to our site, we get 10% commission from Bookshop.org, whose fees support independent bookshops.

Non-Stop Artillery and Drone Attacks

The film’s title – Human Safari – is devastating. Can you talk about where that phrase came from and what it signifies?

I remember very well when I first heard this phrase in Ukrainian. I went to the area near the river, and it was hard to find someone who’d risk driving there. Tetiana, an energetic woman in her 60s, took me around the high-rise, showing the aftermath of non-stop artillery and drone attacks, talking fast, almost running, pointing at broken windows, walls, doors, and debris scattered among the grass.

She told me that she could not go visit her recently deceased husband’s grave as the Russian drones hovered and followed her. “Safari on people” was the exact Ukrainian phrase she used, and when I came home, as I was writing the article for Byline Times, it took me some time to choose the right words in English. Since then, sadly, “human safari” has become a part of the modern vocabulary. The idea of claiming the authorship appalls me, to be honest.

Human safari is a war crime and a crime against humanity, now recognized by the UN and Human Rights Watch. Intellectual right on atrocity is immoral. Putting “human safari” in the film title was our editor’s idea. Artem Tsynskyi, a Ukrainian filmmaker and theatre director, is my co-author, and I am grateful for his idea. Even though the film covers the whole history of Kherson, and the human safari is just one chapter of it, it really worked.

It is Not About a Journalist’s Feelings

The film is an act of witness. What responsibilities come with documenting war crimes, especially when the world is becoming numb to conflict?

“Numb to horror” could be a good title for an article or a book. It is so true. Human psychological defence mechanisms are remarkable – and, perhaps, are there for a reason, to protect our fragile psyches from the unspeakable horror of reality. So, breaking through these defences is one of the hardest parts of the reporting process. The on-the-ground reporting is easier, at least for this reporter. An attack or a war crime happens, and you are there to record and report it.

Say, you speak to a woman injured by a drone or a torture survivor. You listen and film or record. Then, you do your best to get the story down as accurately as possible. You verify facts and details. Then you edit; in the case of film, you decide what makes it into the final cut and what doesn’t. It could be hell emotionally, but it is a part of the job. It is not about a journalist’s feelings.

The hardest part comes after the report is finished. Convincing editors to publish it is hard. I am very lucky with my newspapers, Byline Times, Euromaidan Press and Fresno Alliance, but with other publications I write for as a freelancer, getting the story about Ukraine out is much harder at this stage of the war. Yet, it is my responsibility to deliver the story to the world and convince the publications to do it, even if the world is not ready.

Sharing Life Under Hourly Shelling

There’s a raw intimacy in the testimonies of Kherson’s citizens’ voices that are often lost in geopolitical analysis. How did you build the trust to capture these stories?

Since I live there, Khersonians became my friends, neighbours, and people I see daily. We share life – and sharing life under hourly shelling can make you close. Although not always – there are still privacy and boundaries. I did not have any particular strategy or a plan but I care deeply about the city, streets, buildings, and people. This matters.

We are all physical beings and connect on a non-verbal level – and this is not something you can fake. Speaking the local languages helps a lot. I am fluent even though I make tons of mistakes and pronounce things wrong but it is not about perfectionism. It is about the connection, about listening and being there.

You Can Feel the Dark Presence in Your Bones

The documentary charts not only occupation and liberation, but the drone warfare that continues today. How has the battlefield changed – physically and psychologically – since the initial invasion?

It is hard to talk about degrees of pain and shades of evil. To me, it is about the ominous Russian presence. They were in the city – and Khersonians could not breathe. So many described to me this physical sensation of suppressed breath during occupation – with the ability to breathe fully returning as the city got liberated. The Russians took the darkness and oppression with them but they are just across the river, still here.

You don’t see them but you hear non-stop explosions, sounds of air raid sirens. You see the rubble, the gray dead piles of dust in what used to be houses, schools, museums – as the long shadows are reaching from across the river. It reminds me so much of Mordor in Lord of the Rings; you can feel the dark presence in your bones and on your skin. And attacks only intensify. Ever since they started on November 14, there have been more and more weapons flying at the city. If we, as the world, do not provide the necessary help, there will be nothing left.

“They will dissipate. It is just a matter of time…”

Attacked by Swarms of Sci-Fi Insects

As a journalist who actively exposed Russian war crimes, how do you navigate personal risk when confronting state narratives so directly?

As any journalist writing about the Kremlin, I was targeted both online and physically, and the only answer I have is my continued work. It is like being attacked by swarms of sci-fi insects – you just keep moving forward, telling yourself this nightmare is not real and waiting for them to dissipate. They will dissipate. It is just a matter of time.

We Are Made of the Past

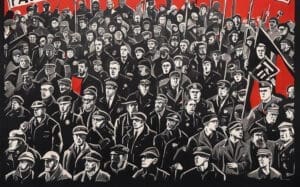

Kherson: Human Safari doesn’t just document the present – it feels steeped in deeper historical echoes. What lingering ideologies or inherited traumas did you sense shaping the ground beneath today’s conflict?

This is a great question. Yes, if it were up to me, I would make this film much longer and dig deep into the ancient history as well as the geography – Scythian myths, Greek epos and archaeological finds, Cossack ballads and Jewish history, imperial and Soviet records. We are made of the past. What we see now is the result of the long alchemical processes. Untangling them thread by thread would be enriching, rewarding, and enlightening.

However, I had to make a war documentary to help save the city, and the urgency demanded limitations. I am hoping to go down the Kherson rabbit – or prairie dog – hole in the book and have already done some reading on the history, archaeology, and folklore. Just studying the old maps or finding out more about the flora and fauna of the steppes is such inspiration. The study of centuries of struggle for freedom is awaiting its scholars.

Real People’s Stories

As well as journalism, you have a background in poetry and fiction. Did your literary sensibility shape the way you produced and directed this documentary?

Absolutely. Journalism comes from the head. Reporting needs to be factual and require logic, clarity, and critical thinking. Literature – prose and poetry – comes from the subconscious, and that’s our bodies. The smell of the river you cannot see, the touch of the sycamore trees cut by shrapnel, the sounds of air raid siren mixing with a birdsong, the taste of the homemade apricot brandy all mix together in the feel of the city – and the atmosphere of the film.

But then, in the documentary, it is all layered and mixed: you just follow the story. When I write novels, I see my characters and they talk to me. I just write things down. In the documentary, I filmed real people’s stories.

Khersonians Speak and Tell their Story

In a world where disinformation spreads faster than truth, how do you see the role of documentary film in countering propaganda?

Our team just let Khersonians speak and tell their story. These are genuine, true voices, and the audience knows it. You can’t fake it. So my hope is to amplify these voices so they are heard and the true story of Kherson is known. The request for help is heard and answered. And the lies and fakes crumble, fall off, and disappear like cheap paint, revealing the raw and real.

Banality of Evil

Has making this film changed your understanding of resilience, especially among civilians who never chose to be on the front line?

Before living in Kherson, I only read and watched films about resilience and resistance during the war. I did see the opposition forces and underground fighting authoritarian regimes in several countries – in some cases, dealing with imprisonment and state brutality. Yet, I have never seen people living daily life under non-stop physical attacks. I can see how mundane it can become while being heroic. It is the other side of Hannah Arendt’s banality of evil. Life doesn’t turn black-and-white during the war; it is as complex, multi-coloured and multi-layered, or more so, as during peace. It is both fascinating and depressing.

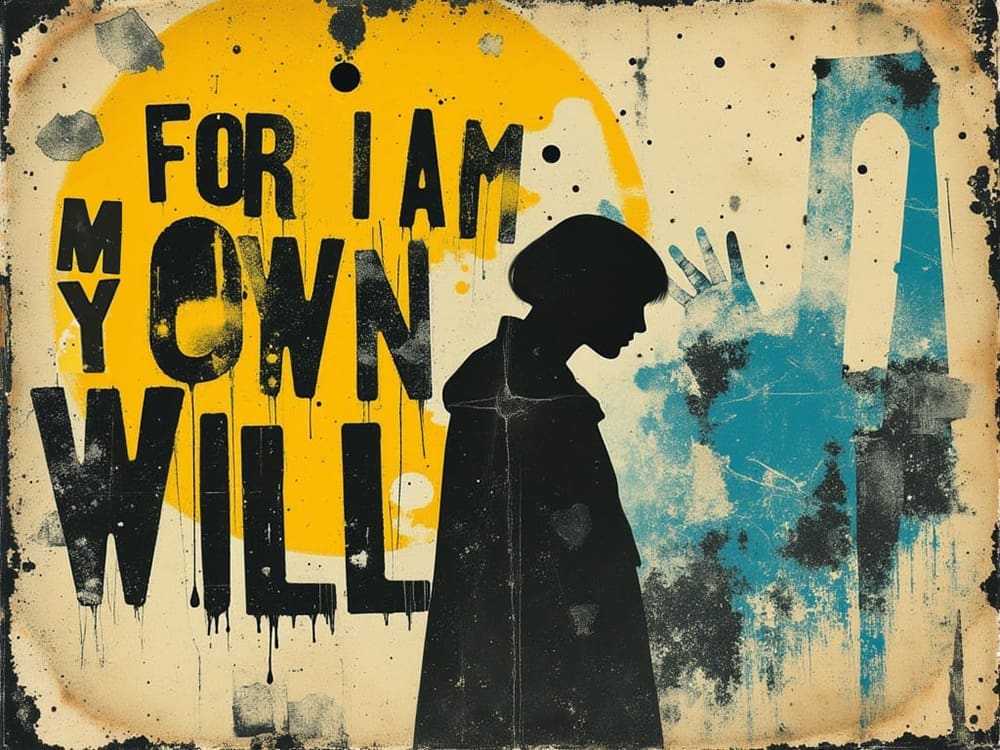

For I am My Own Will

With this level of violence and systemic cruelty, how do you guard against despair? What keeps you going as a witness?

I would say it is rage at injustice and ultimate belief in one person’s agency. There is a graffiti on Freedom Square – “For I am my own will.” We can change the world and stop evil. The people of Kherson are proving it. I am lucky and honoured to be there to record it for others.

Reputational Security for Kherson

Looking forward, how do you want Kherson: Human Safari to be used – in schools, courts, memory? What is your hope for its legacy?

I am not thinking of legacy. I want this film to become a weapon to fight for Kherson now. Peter Pomerantsev, a British scholar, shared the concept of reputational security. Simply put, if the world knows and cares about the place, it is harder to destroy it. I hope our documentary will establish reputational security for Kherson.

I am writing this on the plane as I am about to speak to decision makers and our elected officials in the US. The plan is to, first of all, get the world to acknowledge human safari – a war crime and a crime against humanity, as it has been confirmed by the UN and HRW reports, and take action. And, not necessarily, in this order. We can still save Kherson – by providing anti-drone defence systems, closing the sky over Ukraine, providing Ukraine with the weapons to push the Russian occupiers back to their territory, and adopting sanctions that would make it impossible for the Kremlin to continue the war of aggression

I also hope that this film – and my other reports – are used at tribunals as a piece of evidence. The legacy… we are not there.

It Will Be Better.

Finally, if someone watches this film and feels overwhelmed or helpless, what would you want them to do next?

Anyone can join Team Kherson and help us fight for the city. Since our number one goal is to raise global awareness, you can share the link to the film on social media or with your loved ones, friends, and circles. Spread the word. Make everyone aware of what is happening. You can write to your elected officials and make them aware of the situation.

There is also a donation page, and in three weeks since the film came out, we transferred enough money to our volunteers – people you see and hear from in the film – enough to evacuate several families and a makeshift animal shelter to safety and find long-term accommodation for them for anywhere from one to two years. It is something tangible. We also bought a boat for the Kherson defenders and collected money for the anti-drone defence fund. So the film is already helping people in Kherson. It is a good feeling. They say in Kherson – “it will be better.”

Many thanks from Pen vs Sword to Zarina Zabrisky for this fascinating conversation

*Visit and Subscribe to Zarina Zabrisky on X

**Visit The Kherson: Human Safari website

***Visit and Subscribe to Zarina Zabrisky on Instagram

What do you think?