activism, activist, ads, Advertising, advocate, art, Artwork, censorship, Ethics, flag, Gaza, Meta, moderation, Palestine, palestine 2023, Peter Kennard, politics, protest, radical, Resistance, social justice, solidarity, Stop the War Coalition

428 Views

Pixels of Protest, Threads of Resistance

A Protest in Pixels: Same Image, Different Judgment

When you run a small ethical business, every detail matters. Every word, every pixel, every decision about what you show the world – and how. So when an ad for a t-shirt runs without issue and an ad for a neck gaiter, using the exact same artwork, gets pulled halfway through its run, the inconsistencies aren’t just annoying – they’re revealing.

This is the story of two ads, one collaboration, and one flag. It’s about art, protest and the strange, shadowy way that platforms like Meta decide what acceptable political expression is, and what gets silenced.

All of our content is free to access. An independent magazine nonetheless requires investment, so if you take value from this article or any others, please consider sharing, subscribing to our mailing list or donating if you can. Your support is always gratefully received and will never be forgotten. To buy us a metaphorical coffee or two, please click this link.

Table of Contents

*All Book Images Open a New tab to our Bookshop

**If you buy books linked to our site, we get 10% commission from Bookshop.org, whose fees support independent bookshops.

The Collaboration

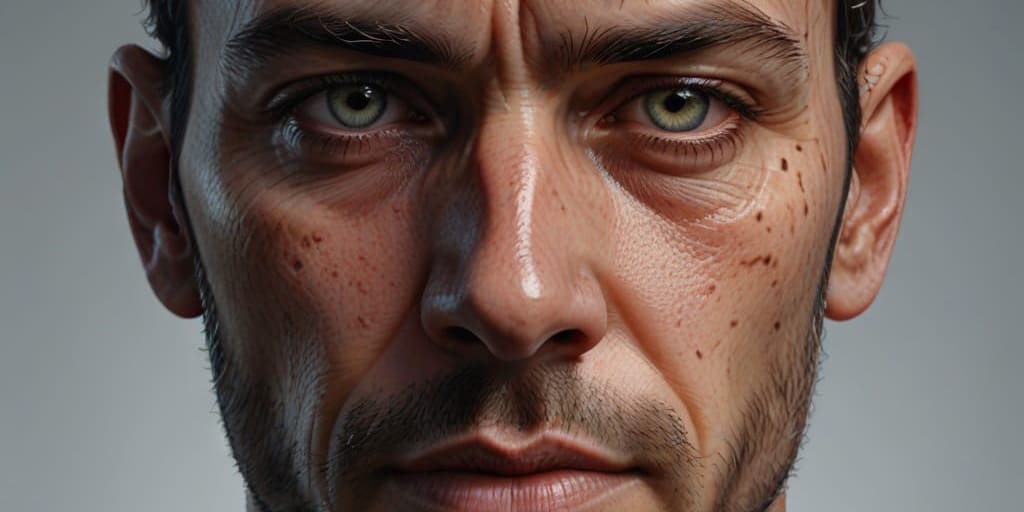

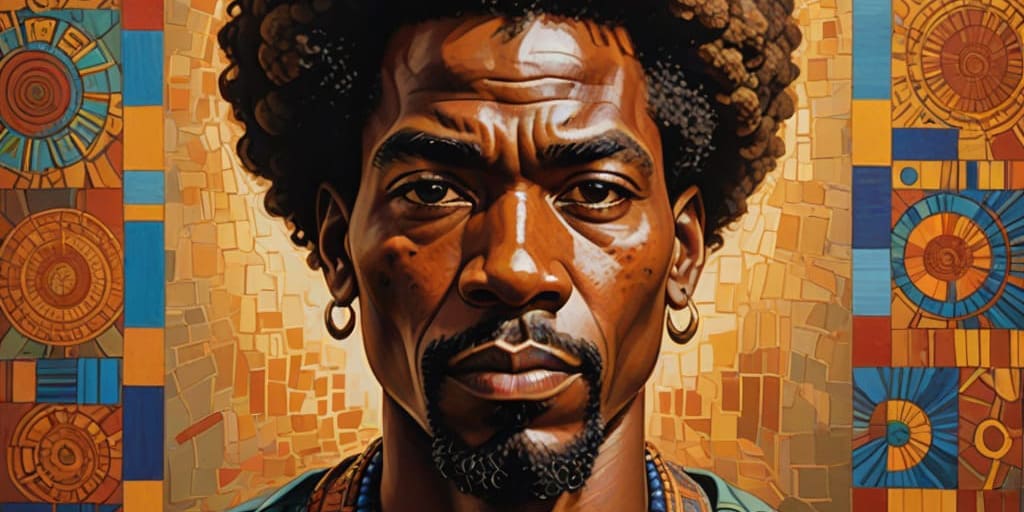

At Souled Out World, our independent fashion and activism project, we’ve had the immense privilege of working with legendary political artist Peter Kennard. His image Palestine 2023 – a powerful interpretation of the Palestinian flag – features in four items from our collaboration: a t-shirt and a neck gaiter.

We agreed from the outset that this project would do more than wear its politics on its sleeve. £10 from each t-shirt and sports jersey and £5 from each gaiter would go to the Stop the War Coalition, an organisation that has previously used the artwork themselves. In every way, this felt right – art, ethics, solidarity.

As with most small businesses, we ran a few low-budget ads on Instagram and Facebook to promote the collection. The ad for the t-shirt ran its course and reached over 87,000 viewers without issue. The neck gaiter ad, however, was flagged halfway through its 4-day run and removed.

The reason? It had been reclassified as an “ad about social issues, elections or politics.”

Political by Design?

Let’s not kid ourselves: Palestine 2023 by Peter Kennard is political. The Palestinian flag – like all national or resistance flags – carries with it decades of history, struggle, loss, pride and complexity. So yes, the image is political. But so was the t-shirt. So is the donation. So is the act of wearing any artwork aligned with a liberation movement.

So why was one version of the image allowed, and the other not?

This is where the problems begin.

The Double Standard

Consider these questions:

- Is the image inherently more controversial when worn over the face?

- Is a neck gaiter read as a symbol of protest, while a t-shirt is seen as passive?

- Does the format trigger different moderation flags within Meta’s ad systems?

The same image, with the same purpose and donation, was treated differently depending on how it was displayed. And this isn’t just a quirk of algorithmic logic. This reflects something deeper.

The Face of Protest

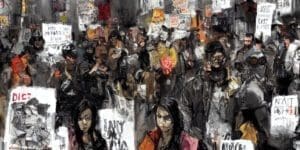

When it comes to visual culture, covering the face has always carried different connotations than baring the chest. A face covering can evoke anonymity, resistance, subversion. Protesters wear them. Rebels wear them. Those resisting surveillance or state control wear them.

The platform, it seems, read the gaiter not as merchandise, but as a message. It was no longer “just art.” It had become a signal of defiance. This interpretation speaks volumes about the politics of optics in digital space.

Moderation or Censorship?

Meta’s guidelines around ads that address social issues, elections, or politics are, in theory, meant to ensure transparency and accountability. But in practice, they create arbitrary and uneven restrictions – especially for small creators.

Larger brands and NGOs can navigate these requirements, jump through the hoops and afford the cost of compliance. But for sole traders and indie shops, there’s no clear path to appeal, explain, or even understand the rejections. In this case, both ads were initially approved. Only one was removed. Why?

Mock-Up Excuse?

One possible explanation might be the use of a digital mock-up. Many small brands use these for ads – realistic images of a product digitally placed on a model. But again, this doesn’t add up. Both the t-shirt and gaiter ads used mock-ups. Thousands of other brands do too.

If mock-ups are a problem, why wasn’t the t-shirt flagged? Why do ads featuring mock-ups flood the platform daily without interference? The rules are not applied consistently. Which means we must consider another possibility: some symbols are more likely to trigger suppression than others.

Palestine, Platform Politics, and Pattern Recognition

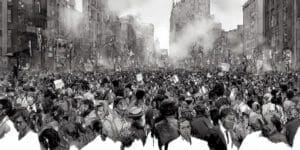

Across social media, there’s a growing archive of stories about Palestinian content being removed, flagged, or deprioritised. From hashtags like #FreePalestine being shadow banned, to live videos of protests being removed without explanation, the pattern is there.

Palestinian identity and solidarity are often algorithmically equated with risk. This makes it harder for creators, advocates, and communities to be visible – especially when platforms err on the side of caution to avoid political controversy or pressure.

When Meta pulls down an ad halfway through, the damage is already done. Attention is lost. Reach is throttled. Messaging is muffled. For a tiny £100 campaign that’s supposed to run four days, that interruption is the difference between being seen and being silenced.

Who Gets to Speak?

The question, then, is not just Why was this ad removed? The real question is:

Who gets to speak freely on these platforms – and who doesn’t?

In a space dominated by private corporations, where content moderation decisions are made by opaque systems or outsourced moderators, freedom of speech becomes freedom by permission. It’s conditional. It’s filtered. And it’s often inconsistent.

This isn’t about “censorship” in the classical sense. It’s about the quiet, unaccountable enforcement of unspoken norms. It’s about how Palestinian symbols, voices and solidarity are made less visible – not always by intent, but by design.

What Happens When Art is Read by Code?

Art is metaphor. It’s context. It’s history. Algorithms, however, aren’t built to understand those layers. They are built to match patterns, flag risks and pre-empt controversy.

To an algorithm, a flag is a flag. A covered face is a protester. A word like “Palestine” is a red flag.

But that flattening is dangerous. When art becomes collateral damage in a war of perception, everyone loses – especially those fighting to be seen and heard.

Pixels of Protest, Threads of Resistance

This incident might seem small. A rejected ad. A lost couple of days. A few missed sales. But what it reveals is significant.

When a t-shirt is fine but a gaiter is political, we’re not talking about fashion – we’re talking about control. About visibility. About who gets to challenge power, and who gets labelled a threat for doing so.

We’ll keep creating. We’ll keep supporting the causes that matter. But it’s time to ask harder questions of the platforms we rely on. Because if an image can be used to silence, it can also be used to speak – louder than ever.

*Browse our full collection

**Donate directly to: stopwar.org.uk

***£10 from every T-shirt and Sports Jersey on this page and £5 from every Gaiter supports Stop the War Coalition

Leave a Comment