Brave New World: A Chillingly Accurate Dystopia

What if the future wasn’t ruled by fear, but by comfort? Not by tyrants and torture, but by pleasure, convenience, and distraction? When Aldous Huxley published Brave New World in 1932, he imagined a world so saturated with ease and engineered happiness that its citizens no longer cared about truth, freedom, or meaning. Nearly a century later, his dystopia feels less like fiction and more like a blueprint – one we may already be following.

In an age of mood-altering apps, algorithm-driven lives, synthetic pleasures, and rising inequality hidden behind sleek technology, Huxley’s warnings ring louder than ever. This article explores the life and legacy of Aldous Huxley, the prophetic relevance of Brave New World and what his work still has to teach us about democracy, unrest, and the price of comfort in the 21st century.

“Huxley’s genius was in predicting that the more powerful threat to freedom would not be oppression, but seduction.”

Margaret Atwood

All of our content is free to access. An independent magazine nonetheless requires investment, so if you take value from this article or any others, please consider sharing, subscribing to our mailing list or donating if you can. Your support is always gratefully received and will never be forgotten. To buy us a metaphorical coffee or two, please click this link.

Table of Contents

*All Book Images Open a New tab to our Bookshop

**If you buy books linked to our site, we get 10% commission from Bookshop.org, whose fees support independent bookshops.

The Making of a Visionary: Aldous Huxley’s Life and Education

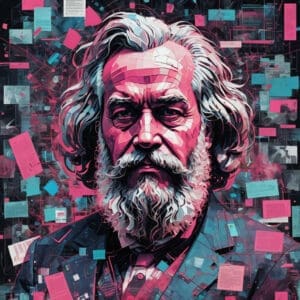

Aldous Leonard Huxley (1894–1963) remains one of the 20th century’s most prescient thinkers and novelists, a man whose intellectual range and foresight placed him far ahead of his time. Best known for his dystopian masterpiece Brave New World (1932), Huxley wrote across genres – novels, essays, poetry, travelogues, and philosophical treatises – and his work continues to shape cultural, political, and ethical discourse in the 21st century.

Though Brave New World often dominates discussions of his legacy, it is not only the accuracy of that singular vision that cements his importance today, but how his broader body of work revealed the undercurrents of modernity: inequality, surveillance, commodification of pleasure, erosion of truth, and the quiet disappearance of individual freedoms behind illusions of comfort.

Born into an intellectually distinguished family in Surrey, England, Huxley was the grandson of the renowned biologist Thomas Henry Huxley, a fervent advocate of Darwin’s theory of evolution. His father, Leonard Huxley, was a writer and editor, and the family moved in elite intellectual circles. This environment cultivated Aldous’s sharp critical thinking and curiosity from a young age.

Educated at Eton College, Huxley suffered a near-blinding illness as a teenager, keratitis punctata, which left him partially blind for the rest of his life and forced him to redirect his ambitions from becoming a scientist to focusing on literature and philosophy. He went on to study English literature at Balliol College, Oxford, where his academic brilliance flourished despite his visual impairments. These early experiences – of physical limitation, elite education, and scientific heritage – laid the foundation for his lifetime concern with the human condition, particularly the tension between intellect, emotion, and power.

From Satirist to Seer: Huxley’s Literary Evolution

Huxley’s early career began with poetry and journalism, but it was his novels that gained him international renown. Crome Yellow (1921), his debut novel, was a satirical look at the hedonistic lifestyles of the British elite in the post-World War I era. Antic Hay (1923), Those Barren Leaves (1925), and Point Counter Point (1928) continued this satirical exploration of a society increasingly adrift from tradition and morality. These novels showed Huxley’s deep unease with the direction modern society was taking, an unease that would crystallize into a more chilling critique with the publication of Brave New World.

Brave New World: A Chillingly Accurate Dystopia

Published in 1932, Brave New World presented a future society where individuality had been sacrificed on the altar of consumerism, technological efficiency, and state-enforced happiness. It was a world without war or want, but also without truth, depth, or real freedom. Through a combination of genetic engineering, psychological conditioning, and the constant administration of the euphoria-inducing drug “soma,” the World State maintained stability and contentment at the cost of humanity’s soul.

The book was controversial upon release, particularly for its critiques of capitalist culture, reproductive technologies, and the loss of spiritual values in an increasingly mechanized world. While George Orwell’s 1984 later presented a terrifying vision of oppression through surveillance and violence, Huxley’s dystopia was subtler and, in many ways, more insidious: a tyranny of pleasure, where people were enslaved not by pain but by their own addiction to comfort.

“Facts do not cease to exist because they are ignored.”

Aldous Huxley

A Mirror for Our Times: Relevance in the 21st Century

The prescience of Brave New World has only grown more striking in the decades since its publication. In our current geopolitical moment – marked by rising inequality, mass surveillance, political apathy, algorithmic control, and the commodification of both truth and identity – Huxley’s warnings resonate with renewed urgency.

His imagined society was not a future of jackboots and prison camps but of pacification through entertainment, distraction, and managed desire. “What’s the point of truth,” the World Controller Mustapha Mond asks, “when happiness is more profitable?” This is a question that seems disturbingly relevant in an age when misinformation spreads faster than facts, when curated digital lives often replace messy realities, and when authoritarianism increasingly cloaks itself in the rhetoric of order, health, and prosperity.

Inequality and Social Engineering: Then and Now

Inequality, a theme that courses through Brave New World, is one of the most visible markers of the global landscape today. The caste system in the novel – ranging from the intellectually elite Alphas to the drone-like Epsilons – was stabilized through genetic manipulation and indoctrination. In the real world, we are not (yet) assigning people to castes in vitro, but global inequality is arguably as rigid and engineered through other means: education disparities, algorithmic bias, economic policy, and corporate monopolies.

Social mobility is declining in many parts of the world, while the concentration of wealth and power in the hands of a few echoes the predetermined hierarchy of Huxley’s world. Even more disturbing is how such inequality is often accepted, or even defended, through a cultural narrative that normalizes consumption and personal gratification over collective justice.

The Tyranny of Pleasure and the Death of Critical Thought

Another striking parallel is the manipulation of public sentiment through pleasure and distraction. In Huxley’s world, the masses are kept docile not through censorship but through inundation – endless distractions, trivial entertainment, and an aversion to critical thought. In today’s media landscape, the line between information and entertainment is increasingly blurred. Algorithms serve us dopamine-inducing content designed to maintain engagement rather than provoke critical thought. As Neil Postman argued in Amusing Ourselves to Death, it was Huxley, not Orwell, who best understood that the real threat to freedom would be our own desire to be entertained into submission.

Unrest, Resistance, and the Illusion of Democracy

Social unrest, too, plays an interesting role in both Huxley’s fiction and our reality. In Brave New World, unrest is something to be managed through pharmacological pacification or removed altogether by isolating the discontent. The “Savage Reservations” are zones of exception, places where the messy realities of life – death, religion, suffering – are confined, studied, and kept out of sight.

Our modern world has its own kinds of reservations: refugee camps, urban ghettos, informal economies, and ignored peripheries where the costs of global capitalism are borne but rarely seen. Protests erupt regularly – from the Arab Spring to Black Lives Matter to pro-democracy movements in Hong Kong and Iran – but are often met with both hard and soft forms of suppression: police violence on the one hand, and performative corporate solidarity on the other.

Pacified Populations and the Crisis of Democracy

In light of current democratic movements, Brave New World is chilling in its depiction of a post-political society. There is no need for voting or representation because the citizens are conditioned to accept their lot and seek pleasure. In the real world, voter apathy is rising, faith in institutions is declining, and many democratic systems appear more performative than participatory. The dangers Huxley foresaw – that a populace might willingly cede its freedom for comfort and distraction – loom large today. The question is not only whether democracy can survive authoritarian threats from above but whether it can survive a populace that no longer values its freedoms enough to defend them.

Aldous Huxley and his Hopeful Vision: Island and the Search for Meaning

Yet Huxley was not a fatalist. In his later works, particularly Island (1962), he offered a counterpoint to Brave New World: a utopia grounded in mindfulness, ecological balance, and spiritual awakening. Though less well-known, Island represents Huxley’s mature philosophy, shaped by his experiments with psychedelics, his interest in Eastern religion, and his enduring belief that consciousness could be expanded, not numbed, in pursuit of a better world. This duality – between the seductions of comfort and the possibility of enlightenment – runs through all of Huxley’s work.

Legacy of a Dystopian Prophet

Throughout his life, Huxley remained engaged with public debates. He moved to the United States in the 1930s and became a cultural critic, pacifist, and later a pioneer in the exploration of altered states of consciousness. His 1954 book The Doors of Perception, which recounts his experiences with mescaline, became a foundational text for the counterculture movements of the 1960s. Though sometimes misread as a mere advocate for drug use, Huxley’s interest in psychedelics was deeply philosophical – he saw them as tools for breaking through the filters of perception that society imposed on the mind. His inquiries into consciousness and spirituality were not escapist but were part of a larger search for truth in a world increasingly defined by illusion.

What Brave New World Got Right – and What It Still Warns Us About

In considering what Brave New World got right, the answer is not simply technological prediction – although its anticipations of reproductive technologies, surveillance-lite societies, and mood-regulating pharmaceuticals are impressive – but rather its psychological and sociopolitical insights.

Huxley understood how freedom could erode not through tyranny but through sedation; how truth could be sidelined not by censorship but by irrelevance; and how inequality could be made palatable through consumption and entertainment. In today’s world – where the merging of surveillance capitalism, social media, climate anxiety, and authoritarian drift creates an atmosphere eerily similar to Huxley’s vision – his work remains essential reading.

True Freedom Cannot be Engineered – It Must be Chosen

His legacy is that of a writer who saw not only where we might go wrong but who also believed in the possibility of doing better. His warnings were not meant to induce despair but to sharpen our vigilance. “Facts do not cease to exist because they are ignored,” he once wrote, and that statement may be his truest contribution to our age of post-truth politics and curated reality.

As we navigate the deep crises of our time – from ecological collapse to democratic erosion to the commodification of consciousness – it is worth revisiting Huxley not as a relic of mid-century anxiety, but as a guide to the psychological and spiritual crossroads at which we now stand. His vision of a “brave new world” was not a prophecy set in stone, but a challenge: to recognize comfort’s shadow, to reclaim meaning, and to remember that true freedom cannot be engineered – it must be chosen.

*Visit The Aldous Huxley Archive

“Brave New World is a blueprint for our own enslavement—one that trades freedom for happiness and meaning for comfort.”

Neil Postman

What do you think?