About the Author

We write image rich articles about Today's Questions and Events that have Shaped Us. Deep Dives into Artists, Wordsmiths, Thinkers and Game Changers. It's Mightier When You Think!

Memory, Siege and the Politics of Survival

Across shifting borders and unbroken memories, Palestine is a story of endurance and erasure. Through writers like Edward Said, Raja Shehadeh, and Susan Abulhawa, this article explores how literature becomes both witness and resistance.

"Our existence itself is resistance, and memory is our longest border"

Susan Abulhawa

All of our content is free to access. An independent magazine nonetheless requires investment, so if you take value from this article or any others, please consider sharing, subscribing to our mailing list or donating if you can. Your support is always gratefully received and will never be forgotten. To buy us a metaphorical coffee or two, please click this link.

Table of Contents

Inherited Borders, Embedded Lives

Every map tells a lie. It is a story of power disguised as geometry, a set of lines drawn by those who claim to know where one life ends and another begins. In The Question of Palestine, Edward Said reminded us that the map of the Middle East was not written in the language of belonging, but in the cold vocabulary of empire. Borders, for him, were instruments of erasure and a means by which the West defined and confined what it did not wish to understand.

Rashid Khalidi, in The Hundred Years’ War on Palestine, takes up Said’s intellectual inheritance and translates it into a ledger of loss. His book is both chronicle and testimony: a historian’s dissection of the long colonial century that has bound the fate of the Palestinian people to the shifting interests of empire – British, then American, each fluent in the rhetoric of liberation while fluent, too, in its opposite.

Between the two voices of Said’s exiled lyricism and Khalidi’s archival precision, out of which emerges the shape of the Palestinian story as it has come to define itself: a people mapped by others, learning to redraw themselves in words.

That remapping is not merely intellectual. It is embodied. In cities from Ramallah to Gaza City, the physical infrastructures of occupation – walls, checkpoints, permit offices – are the cartographic proof of a political claim. As Ilan Pappé documents in The Ethnic Cleansing of Palestine, these infrastructures have a history: they were not accidental outcomes but planned continuities in a logic of exclusion. The maps of the present recall the blueprints of a past engineered to separate, to classify, and to control.

Origins and Afterlives

History, as Pappé reminds us, is not an abstraction, it is an inventory of names, villages and vanished homes. The Nakba of 1948 was not simply a moment of exodus, but the foundational trauma from which the modern Palestinian identity was forged. Pappé’s relentless archival work does more than recount the displacement; it exposes the bureaucratic machinery that made it systematic – an administrative, premeditated cleansing cloaked in the language of necessity.

For Ghada Karmi, that machinery became personal. Her memoir Return is both a journey and a wound – the story of a woman who, decades after being uprooted from Jerusalem, tries to reclaim the geography of her childhood and finds only checkpoints, settlements, and a disfigured horizon. “Return,” she writes, “is never what we imagine. It is not a homecoming but a reckoning.”

Ilan Pappé and Ghada Karmi lay bare a crucial afterlife: the persistence of dispossession in law, memory and materiality. The legal scaffolding of the post-war world – the 1949 Fourth Geneva Convention, the countless UN resolutions such as Resolution 194 on refugees -promised remedies that have, in practice, been partial, contested and deferred. Noura Erakat’s Justice for Some explains how international law is both a resource and a trap: it articulates rights yet depends on enforcement mechanisms that states can, and often do, deny.

That denial has consequences. Refugee camps become permanent through omission. Generations grow into statelessness. The political vocabulary available to Palestinians and their allies is crowded with terms that describe the problem but not the cure. The result is an afterlife that is lived daily: in denied property claims, in ruined olive groves, in bureaucratic forms that must be renewed like wounds.

The authors on our Promises Books Palestine bookshelf insist that memory, testimony and law are interdependent. Without testimony, law becomes abstract. Without law, testimony risks being dismissed. Together, they constitute a counter-archive – an effort to keep the Nakba present, to translate loss into claim, to assert that history demands remedy as well as remembrance.

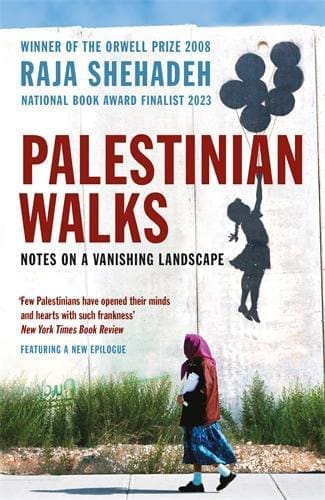

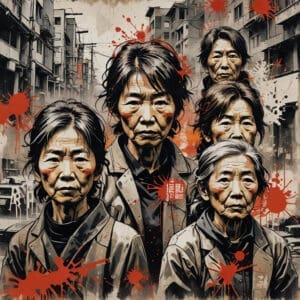

The natural beauty of the land collides with the relentless creep of settlements

Fragmented Geography

Few writers have mapped this fragmentation with such quiet precision as Raja Shehadeh. In Palestinian Walks, his reflections on hiking through the hills of the West Bank become a meditation on vanishing space – where the natural beauty of the land collides with the relentless creep of settlements. His prose carries the ache of the lawyer, the poet, and the witness. “Each time I return to the hills,” he writes, “they are smaller, the sky more hemmed in.”

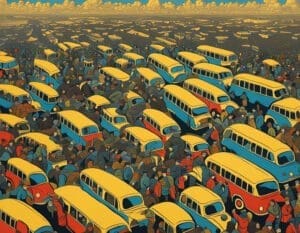

Saree Makdisi, in Palestine Inside Out, expands this landscape into an anatomy of control – a portrait of daily life governed by permits, checkpoints, and invisible bureaucracies. He calls it the “architecture of occupation”: an intricate web of restrictions that turns ordinary acts – travel, work and family – into quiet rebellions. The seam zone, the area next to the separation barrier, the permit offices and the settler bypass roads: these are the instruments by which geography becomes policy.

Consider the permit regime: a system that determines who may access hospitals, universities, markets or religious sites. The permit is a modern talisman, a piece of paper that can be the difference between life and death for a patient in need of specialised care. It is also a political device: to gate movement is to gate possibilities, to freeze livelihoods and fragment society. In East Jerusalem, residency revocations and demolitions translate legal technicalities into forced expulsions. In the West Bank, the creeping presence of settlements reorients roads, water resources and labour markets to the benefit of settlers and the detriment of Palestinians.

This fragmentation is not simply spatial; it is temporal. The lives of Palestinians are punctuated by queuing at checkpoints, by permit renewals, by the constant calculation of risk. Children grow up learning the geography of control before they study maps. The result is a daily politics of negotiation and improvisation: farmers rerouting to avoid settler violence, teachers adapting to curfews, health workers navigating closures to reach clinics.

Yet our booklist also records counter-geographies: olive-press cooperatives circumventing land seizures, community-led water projects and educational networks exchanging resources across fragmented territories. Fragmentation produces improvisation – not merely survival but creative governance born of constraint.

Gaza Now: Siege, Survival and the Human Landscape

Gaza is now one of the most acute experiments in constrained existence. The enclave, home to over two million people in a space of less than 365 square kilometres, has endured blockade since 2007. Its infrastructure, already fragile, has been devastated by repeated military offensives; its energy systems fail daily; water is undrinkable; unemployment is crippling. Reports from humanitarian organisations describe an enclave on the brink, where medicine is scarce and mobile hospitals are stretched beyond capacity.

Susan Abulhawa’s Mornings in Jenin begins as fiction but reads as lived truth – a family saga that captures the continuum between displacement and siege. Her fiction shapes how readers feel the human scale of structural violence: households in which love and survival coexist, children whose first memories are checkpoints and power cuts.

Refaat Alareer, whose contribution to Gaza Writes Back gave the world an uncompromising literary archive of the region, wrote stories that converted rubble into narrative and fear into communal testimony. His work and his death – killed during an Israeli airstrike – became symbolic: the writer as witness, the witness as casualty, the casualty as a provocation to conscience.

"Occupation is not just about land; it is about the slow erosion of a people’s time"

Raja Shehadeh

Reports from the ground underscore the scale of the crisis: hospitals operating at sustained emergency footing, truncated vaccine schedules, schools converted into shelters, and the psychological toll on children exposed to repeated trauma. International agencies have described Gaza’s health system as “on the brink of collapse” and warned that reconstruction would be an era-long task requiring durable access, materials and political will.

Gaza’s political governance adds complexity. Hamas’s control of Gaza since 2007, after a violent split with Fatah, has been one factor in the enclave’s isolation. The internal Palestinian political fracture – mirroring external pressures – complicates reconstruction, governance and advocacy. Egypt and Israel maintain strict controls over border crossings, and the permeability of the border has become a contested diplomatic issue: when and how aid enters, who inspects materials, and what oversight is allowed. NGOs find themselves negotiating a morass of security demands, logistical restrictions and political constraints.

Gaza’s writers document not only suffering but imaginative survival

Human Creativity Under Pressure

The mental and cultural life persists. Musicians perform using salvaged instruments; poets write in dark rooms with flickering generators; filmmakers upload short documentaries when internet permits. These acts are not merely aesthetic: they are forms of testimony, community building, and refusal. Gaza’s writers document not only suffering but imaginative survival – rooftop gardens, community kitchens, youth organisations teaching coding between air-raid sirens. The literature from Gaza, collected and anthologised by editors like Alareer, reframes siege as intensifying not only loss but also human creativity under pressure.

International legal debates swirl around Gaza. The humanitarian vocabulary – collective punishment, sieges, proportionality – permeates UN reports, human-rights literature and court filings. Noura Erakat’s legal work highlights this dissonance: law diagnoses abuses but offers little immediate remedy in the absence of enforcement. Norman Finkelstein’s forensic tone in his critiques of Gaza’s cycles of violence points to a bitter reality: even where legal frameworks exist, politics often determine whether accountability follows.

To be Palestinian in Gaza is to inhabit a geography made by denial: of movement, of sovereignty, of basic resources. Yet it is also to witness the persistence of everyday dignity. The writer and the baker, the teacher and the medic, build the social scaffolding that keeps communities from dissolving into despair. The question the list’s authors return to is not whether Gaza will survive in some technical sense but whether dignity and rights can be restored in ways that make renewal possible.

"To be Palestinian is to keep one eye on the key and the other on the horizon"

Mourid Barghouti

Barriers: Law, Power, Narratives and Geopolitics

The systemic barriers to Palestinian rights multiply like borders. First, the law: occupation is regulated by international humanitarian law in theory but often ignored in practice. The Fourth Geneva Convention, the Hague Regulations – these instruments outline duties of an occupying power but rely on states and international institutions for enforcement. Noura Erakat shows how legal claims are frequently boxed in by political realities: legal victories are applauded in courts but then neutralised by diplomatic manoeuvring or by a lack of enforcement mechanisms.

Norman Finkelstein’s Gaza: An Inquest into Its Martyrdom lays bare the politics that mute legal sanctimony and mute calls for accountability. Finkelstein, in his provocative bluntness, documents the selective nature of outrage – how similar acts in different contexts are judged under different standards. His work is a study of the double bind: law as both tool for justice and instrument of legitimation when deployed selectively.

The Security Council’s paralysis – vetoes, geopolitical bargaining and the prioritisation of state sovereignty over individual rights – has repeatedly stymied decisive action. States invest in arms deals and strategic alliances that shield allies from the consequences of policy. As Avi Shlaim’s The Iron Wall explains, security doctrines, once articulated as defensive strategies, calcify into doctrines of impunity over decades.

Narrative is also a critical barrier. Edward Said’s analysis shows that the distribution of narrative power – who gets to name, photograph, and humanise – shapes public sympathy and policy. Media representation often flattens Palestinians into either perpetrators or victims, rarely granting them full subjectivity. Studies of news coverage routinely find differential treatment in how victims are named, contextualised and empathised with.

Politics is Heavily Influenced

Geopolitics compounds these dynamics. The shifting alignments of regional powers – Egypt’s security concerns, Qatar’s mediation, Iran’s regional posture, Gulf states’ normalisation deals with Israel – reshape the contours of what is diplomatically possible. Arab normalization with Israel, pursued by states like the UAE and Bahrain, has undercut regional leverage for Palestinian statehood and complicated solidarity strategies.

External patronage fuels internal fracture. Aid flows and donor preferences often incentivise governance forms in the Palestinian Authority that prioritise short-term stability over institutional reforms. The PA’s dependence on foreign aid and its political contest with Hamas, creates a governance environment where politics is heavily influenced by donor conditions. Ramzy Baroud’s work on diasporic networks shows how external funds create parallel structures of power that can both support and distort local agency.

Then there is the economic blockade: restrictions on cargo and people, export bans, limits on fuel and construction materials – all of which hamper reconstruction, business and agriculture. The Israeli designation of certain materials as dual-use has meant that even basic items for rebuilding are scrutinised and sometimes denied entry. The logic is strategic: deprivation as management.

Finally, the arms trade offers a practical barrier. Where states continue to supply weapons and intelligence, pressure for accountability diminishes. The international system is structurally biased: states trade with each other while people pay the human cost.

The authors on our bookshelf map these barriers not as isolated obstacles but as a network. The architecture is more than physical; it is legal, economic, narrative and diplomatic. Tearing down one wall will not suffice; all the supporting pillars must be addressed.

Acts of Everyday Resistance and Cultural Life

In the booklist’s rich array of memoirs, poetry and reportage, one recurring theme is that the Palestinian experience is not just of entrapment – it is of creation. Culture, in these texts, is counterpower. When legal claims falter, stories persist; when movement is restricted, memory moves; when land is lost, identity remains.

Mourid Barghouti’s I Saw Ramallah captures the estrangement and small triumphs of return: walking on a street that keeps the shape of your childhood, hearing a language that strains to recognise you. Mahmoud Darwish’s poetics, from the lyric insistence of “We have on this earth what makes life worth living” to the elegiac Memory for Forgetfulness, remains the heartbeat of Palestinian literary identity. Through Darwish, the quotidian becomes sacred; through Barghouti, the return becomes a moral rehearsal rather than a final destination.

Contemporary cultural activism multiplies these voices. Young Gazan filmmakers upload short documentaries when internet permits; West Bank rappers produce songs that circulate in underground networks and across social media; East Jerusalem visual artists mount exhibits that travel to diaspora galleries. Ahdaf Soueif’s Mezzaterra describes this cultural in-betweenness: art as the steady work of reasserting identity across dislocation.

"We write because life does not suffice, and because the homeland is still a sentence unfinished"

Ghassan Kanafani

Community initiatives provide another register of resistance. Cooperative olive presses, community health clinics, popular education programmes and local environmental projects offer not just survival but the scaffolding for a civic life. In Gaza, rooftop farming initiatives attempt to reclaim food sovereignty amid import restrictions. In the West Bank, community land trusts resist displacement. These initiatives often receive little international attention but are vital to social reproduction.

Education is also a frontline. Palestinian universities, under siege conditions or occupation restrictions, become hubs of resistance and intellectual production. Youth organisations teach human rights, digital literacy and civic engagement, preparing a generation for both political participation and cultural renewal.

These acts of everyday resistance are not romanticised by the writers; rather, they are shown in their gritty complexity. Resilience exists alongside fatigue, creativity alongside trauma, small victories alongside systemic setbacks. The literature insists that culture and organisation are the twin engines of future possibility.

Diaspora, Memory and International Solidarity

The Palestinian diaspora is one of the largest – and longest – refugee experiences in modern history. Authors on the list treat diaspora not as a footnote but as central to the Palestinian identity: a network of return, of remnant families, of communities living between exile and home.

Leila Khaled’s memoir My People Shall Live offers the radical edge of that bridge – a portrait of resistance from one of the most iconic figures of the Palestinian struggle. Whether one agrees with her methods or not, Khaled represents how diaspora politics can bridge the symbolic and the strategic. Ramzy Baroud’s These Chains Will Be Broken offers a more collective record: oral histories of prisoners and families that map resistance as a social phenomenon spanning detention centres, refugee camps and living rooms.

Diasporic activism is not uniform. In the UK, Palestinian-British communities lobby MPs, fund legal challenges and archive family histories. In the US, Palestinian-American writers and students have driven BDS debates on campuses, catalysing broad conversations about solidarity and free speech. In South Africa, memory politics connects the Palestinian cause to apartheid histories; legal activists there have pursued cases linking occupation to human rights violations.

Solidarity is both powerful and contested. The Boycott, Divestment and Sanctions (BDS) movement has shifted commercial and cultural terrains, prompting debates about the ethics of engagement and the role of economic pressure in human-rights advocacy. Cultural boycotts, statements by artists and academics, and institutional divestment offer strategic pressure points that bypass state diplomacy. But solidary tactics also trigger backlash: accusations of anti-Semitism, governmental restrictions on advocacy, and legal measures to criminalise aspects of solidarity activism.

The booklist’s writers emphasise that solidarity must be principled and sustained. It should not be performative or fleeting; it must translate into political pressure, legal action and material support. Memory work such as oral histories, archives and museum exhibits developed by diaspora communities create enduring records that counter erasure and foster transnational political movements.

Between Memory and Futures

To read the works of Said, Darwish, Karmi, Khalidi, Shehadeh, Erakat, Alareer and the others is to traverse a living map – not of borders but of voices. Each book reclaims a fragment of geography, a memory, a right to narrate. Together, they form what Said called a “contrapuntal” symphony: history and resistance, poetry and law, exile and belonging.

In today’s geopolitical moment – where the same powers that preach human rights remain silent before their erosion – these voices become more urgent, not less. The struggle for Palestine is no longer just about a strip of land; it is about the moral coordinates of our shared world.

When Refaat Alareer wrote, “If I must die, let it bring hope,” he was not speaking only for Gaza. He was speaking for all those who refuse to be defined by their erasure.

Perhaps this is the truest legacy of Palestinian literature: that it transforms suffering into testimony, testimony into art, and art into the stubborn insistence that another map – one drawn in justice – remains possible. That map will not be inked by diplomats alone; it will be built in classrooms, courts, farms, archives and kitchens – by people who refuse the amnesia of power.

In the end, to read Palestine is to be summonsed into witness. It is to recognise that history has not finished being written, and that a people’s claim to dignity is not a plea but a right. The work, as the writers insist, continues – through pages, protests, and passageways – until the geography of power yields to the geography of justice.

Browse 4000+ Books in Our PromisesBooks Bookshop

About the Author

We write image rich articles about Today's Questions and Events that have Shaped Us. Deep Dives into Artists, Wordsmiths, Thinkers and Game Changers. It's Mightier When You Think!

Post Comment